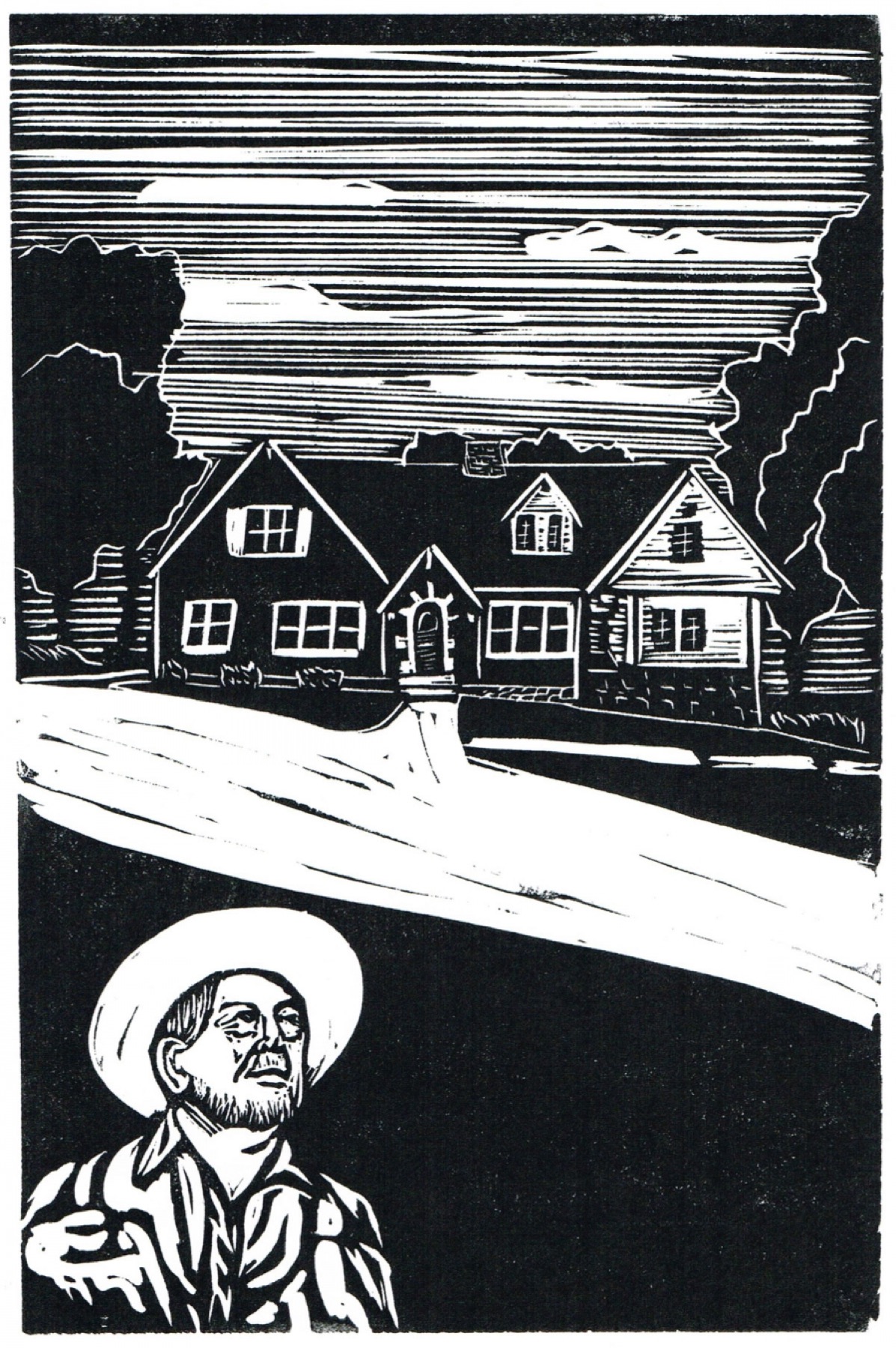

Illustration of Cowboy Jack Clement by Julie Sola

SINS FORGOT

By Peter Cooper

Scenes from Cowboy’s Place

An excerpt from Johnny’s Cash & Charley’s Pride: Lasting Legends and Untold Adventures in Country Music, available April 25 from Spring House Press. Reprinted by permission of the author.

If I had Johnny’s Cash and Charley’s Pride

I wouldn’t have a Buck Owen on my car—Cowboy Jack Clement

We should probably start with the Cowboy. He’s the one you should have met. We all called him a genius. He neither confirmed nor denied. “I ain’t saying I’m a genius,” he’d parry. “But you’ve got to be pretty smart to get all them people saying that on cue.”

A bullshit artist, sure, but with emphasis on the “artist” part of that equation. He discovered Charley Pride, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Don Williams. He wrote songs recorded by Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, Ray Charles, Porter Wagoner, Jerry Garcia, John Prine. He owned the world’s smartest cat, and the world’s greatest accordion player lived in his backyard. He ran the Cowboy Arms Hotel & Recording Spa, Nashville’s first great home studio, where Cash, Townes Van Zandt, Alison Krauss, Nanci Griffith, John Hartford, and a bunch of others recorded and cavorted. He engineered the 1956 “Million Dollar Quartet” session at Sun Records in Memphis, capturing the jovial interactions of Cash, Jerry Lee, Carl Perkins, and Elvis Presley.

He watched his house—the one with the studio, and hundreds of priceless master tapes and the photo of him saluting Princess Elizabeth in his Marine days and the Gibson guitar with the scuff marks from Elvis’s belt buckle—burn down. He just stood there out in the yard, wearing his Elvis Presley bathrobe. Singer and dear friend Marshall Chapman heard the furious sirens and joined Cowboy out there in the yard, grimacing at the leaping flames. First thing he said to her was, “Want to buy a house?”

Cowboy Jack Clement.

Everybody called him “Cowboy” even though he wore comfortable shoes and was frightened around ponies. “They’ll kick you and bite you, and step on your toes,” he sang. “Some cowboys hate horses, and I’m one of those.”

There’s a documentary film about him. It’s called Shakespeare Was a Big George Jones Fan. He liked making home movies, and he’d get his friends to star in little skits for him. He also blew a cool million one time, making a horror film called Dear Dead Delilah. He later admitted that he probably should have written a script, or at least should have had someone else write one.

Cowboy name-checked Shakespeare in one of his songs and he often quoted the Bard. His devotion, though, was neither blind nor complete. He’d rattle off the To be or not to be line, and the one about the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, but he couldn’t go all in on Be all my sins remembered. “Don’t hand me all this shit about all my sins remembered,” he’d say. “I want my sins forgot.”

He was Nashville’s Polka King. When asked how he got that title, he’d say, “I just started calling myself that, and nobody argued.”

He drank vodka and smoked what I’m told was the best dope in town.

He arranged the horns and played the guitar on Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire.”

He owned the Dipsy Doodle Construction Company.

For a brief while, he owned Summer Records. Company motto: “Summer hits, and summer not. Hope you like the ones we got.”

He was an Arthur Murray dance instructor, and he got the gig in spite of having no knowledge of how to dance. He learned, though, and he’d dance in the recording studio with a wine bottle on top of his head, if the music was going well and there was a wine bottle handy. Turns out there was always a wine bottle handy, although the music didn’t always go well.

He was Waylon Jennings’s brother-in-law for a while, and he produced what Waylon said was the best album of his career: 1975’s Dreaming My Dreams.

For decades, whenever any writer, picker, or dime store philosopher came to Nashville, they’d quickly find their way to 3405 Belmont Boulevard, Cowboy’s place. You couldn’t miss it: There was a swimming pool there, and a bunch of cars parked in the circular driveway, and any manner of things going on inside. Somebody would be building a ukulele, somebody would be making a movie or a record, and Cowboy would either be in the middle of it all or he’d be by himself in his office, listening to music on his speaker system.

In the 1970s, a Texas songwriter named Eric Taylor—a brilliant and occasionally wayward soul—visited Cowboy in hopes of getting a publishing deal. See, Cowboy published songs, too. He published one of George Jones’s biggies, “She Thinks I Still Care.” And he published songs for Eric’s friend Townes Van Zandt.

Eric sits down and plays a song called “Joseph Cross” for Cowboy. “Joseph Cross” is seven minutes of poetry, myth, and wonder about the treatment of Native Americans, which Eric just calls “terrorism.”

“His name was Joseph Cross, and he was raised by the mission,” Eric sings. “Just one of a hundred Indian boys that wouldn’t tie his shoes.”

So, Eric played “Joseph Cross” for Cowboy, whereupon Cowboy asked Eric, “Boy, do you know where you are?”

Eric said he thought he knew where he was.

Cowboy asked again, “Boy, do you know where you are?”

Eric looked confused, so Cowboy talked some more.

“Boy, I’d heard your music before you got here. I like you, my wife likes you, and my girlfriend likes you, too. But if I’m not mistaken, you just played me a seven-minute song about an Indian. Is that right?

Eric agreed that he’d just played a seven-minute song about an Indian.

“If you don’t know where you are, I’ll tell you. You’re in Nashville By God Tennessee. I couldn’t sell a seven-minute song here if it was about screwing.”

Eric decided to go on back to Texas after that.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.