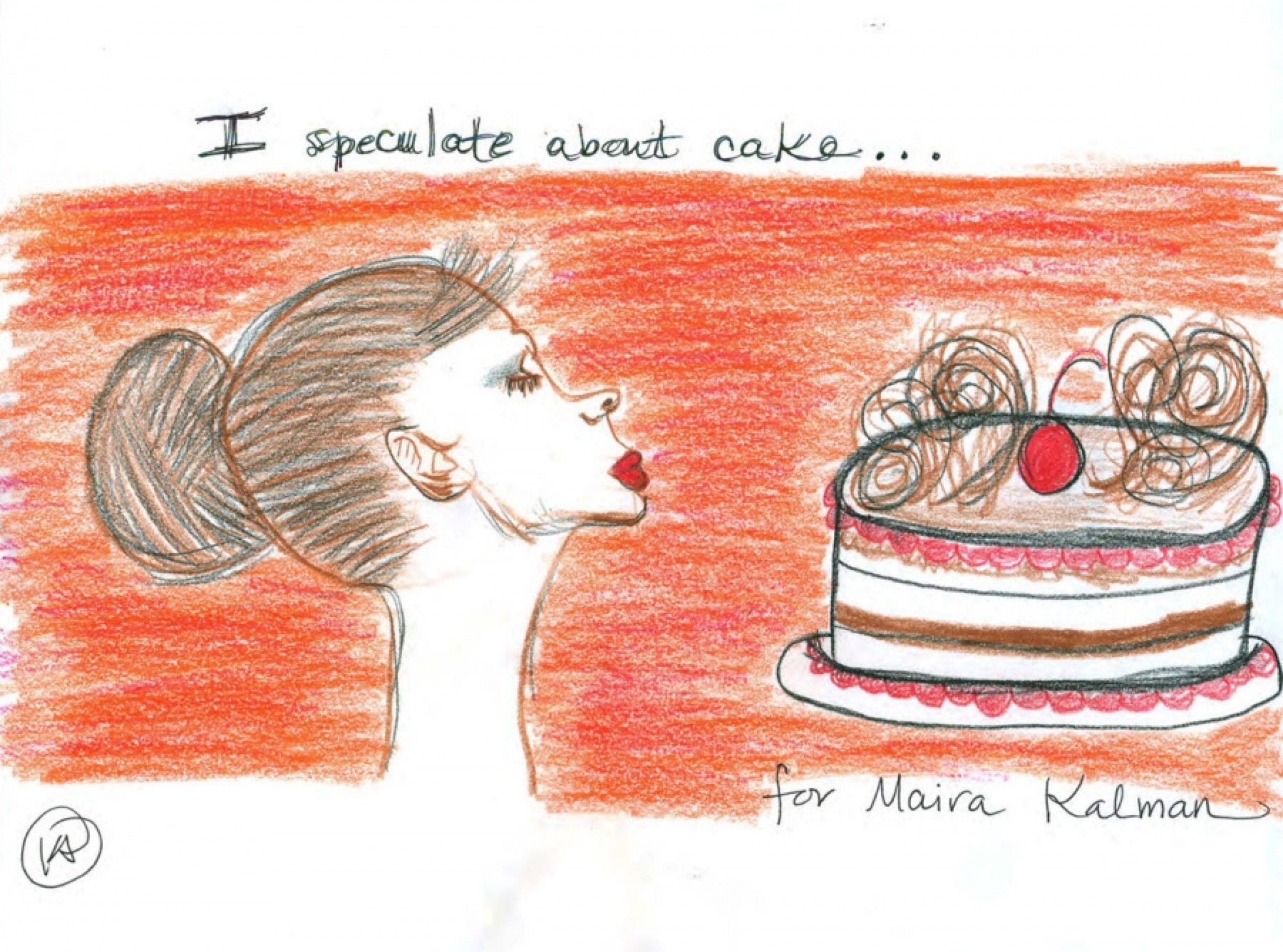

Illustration by Kelly Alexander

HALF-CAKED

By Kelly Alexander

A Dispatch from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University

Dear Reader: This essay is dedicated to Maira Kalman, the illustrator and author. Kalman’s recent talk at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) on her creative process inspired me to finish this piece, which I’d started long before I knew of Cake (Penguin Press, 2018; with recipes by Barbara Scott-Goodman). Kalman’s book proves what I’ve always believed: Cake is a most social food. We will be reading the book in my fall course at CDS, Our Culinary Cultures, when we talk about food in terms of its symbolism and imbued meanings. The students will write essays about an experience they’ve had with cake and “cake,” and will research at least one recipe, including details about its history and origins. À la Kalman, they will be required to illustrate their essays, as I have illustrated mine.

—Kelly Alexander, CDS undergraduate education instructor

CDS editor’s note: Kelly’s perennially over-enrolled writing seminar, Our Culinary Cultures, is one of around fifty Documentary Studies courses offered annually through our undergraduate education program. Every year, faculty and visiting artists—all practicing documentarians—teach some eight hundred fifty students from all majors who are drawn to CDS for classroom mentorship and immersion in community-based fieldwork.

All kinds of foods can capture one’s imagination and open doors into sensual memories—inspiring possibilities for things to cook up, both literally and metaphorically. This is even true for food writers like me who spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about food, yet can still take off on a flight of fantasy over a dish or ingredient. For example, a couple of years ago I was thumbing through a raggedy magazine in a pediatrician’s waiting room with my ten-year-old son when I came upon a remembrance of the novelist Pat Conroy by the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Rick Bragg. Bragg, who is from rural Alabama, says that early in his career he formed a kinship bond with Conroy, a military brat who spent his teens in Beaufort, South Carolina. For years the two corresponded, forming a loose Southern brotherhood of men of words. Bragg recalls an occasion in which Conroy drove across the Georgia-Alabama line in order to have dinner with Bragg and his mother: Conroy and his wife showed up with half of a cake.

Bragg mentions the cake as a way to show that Conroy was the sort of freewheeling dude who thinks nothing of showing up with an incomplete offering, because his charm can carry the day. (As it went on to do.) But it really struck me, that half cake. It is a common custom throughout the world of course, and perhaps especially in the South, to bring a “hostess gift” when one is invited to dinner. What led Conroy to go with half a cake, I wondered—and what role did the gift play at that gathering? Beyond its obvious necessity as sustenance, what role does any food play in our lives? The cultural anthropologist Jon Holtzman argues that food is perhaps the most crucial material for understanding human social life—an edible epistemology, or way of knowing if you will, about what people value and why. If that’s true, then what is the meaning inherent in a fraction of a food? Is it more than nothing, but less than something?

And what kind of cake was it? Bragg says German Chocolate Cake. A showstopper, tall and leggy, with the frosting equivalent of a bouffant hairdo. It is not a stretch to see Conroy choosing it. As it happens, German Chocolate Cake is not even from Germany. It was christened “German Chocolate Cake” by a baker from Dallas, Texas, in honor of a chocolatier named Samuel German. German Chocolate Cake is not for everyone, but it can probably handle a road trip: The sweetened evaporated milk, sweetened coconut flakes, flecks of chopped pecans, and extra egg yolks bind it well, and so it’s possible to picture it—or half of it—in a big white box riding shotgun, rolling down a southeastern stretch of I-20 West. On second thought, I wondered why Conroy hadn’t chosen a more travelable dessert—that way he might have been able to bring the whole thing. Think of a pound cake, wrapped in waxed paper and resting in a brown paper bag, its butter slowly turning the sack greasy. Pound cake has a lot more utility and a lot less volume than German Chocolate Cake; you can eat a slice for a snack or for breakfast without making a production of it, and you wouldn’t even have to hold it on your lap during a car trip.

And how about the cake’s other half? Bragg admits that he doesn’t know for sure what ever became of it, and that his mother was too polite to ask. If Conroy and his wife didn’t eat it, did they go into a bakery and say something like, “We’ll take something European-sounding, a German Chocolate Cake or a Black Forest Cake if you have it, but just half?” Now Black Forest Cake actually is from Germany. Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte gets its name from kirschwasser, the cherry liquor produced in the forested outskirts of the city of Bonn. Black Forest Cake is notoriously difficult to transport because it has a crown of giant chocolate swirls, brandied cherries, and whipped cream sitting on top of it. Imagine trying to keep that sucker—err, part of that sucker—reasonably intact while you’re bombing your way toward Calhoun County, Alabama.

I couldn’t shake intrusive thoughts about the cake, although before I knew it I had to drop the reveries in favor of the strep throat at hand. A few months later, I ran into a book publicist who works with many Southern writers. I asked her if she knew either Bragg or Conroy and explained my curiosity. “Well, if you want to find out more about the other portion of that cake, I can get you Cassandra King’s email, and you can ask her yourself,” Katharine said. Cassandra King is, in addition to being Pat Conroy’s widow, a noted novelist in her own right. Hell yes I wanted Katharine to reach out to her. Or so I thought. Because when I obtained the email address, I found myself unable to use it; it seemed crazy to reach out to a stranger who’d just lost her husband with a trifling question about a cake. I let it sit. Months later, I finally got up the gumption to email Ms. King. She wrote back with her phone number and said that if I called, she’d fill in the details about what happened to the rest of the cake. Yet when push came to shove, I still couldn’t bring myself to pick up the phone. I was stuck. If I got the answer, I’d have to stop envisioning all the ways that the cake might have made its way to Bragg in the condition that it did, and all the possibilities of what happened to the rest of it. It’s not that I didn’t want to know—I wanted to know even more than I want to know why no one else in my household can remember to put the toilet paper on the roll. It is that in the intervening months—now years—since I had read Bragg’s homage to his late friend Conroy, I had discovered something. Speculation is delicious. Meditating on half of a cake, pondering its varieties and iterations, contemplating its value as an edible commodity and a social comestible . . . that is pure pleasure. An answer is satisfying, but speculation is limitless. The daydreaming I still do about the mysterious and unaccounted for missing half of that cake brings me more joy than the facts about what happened to one cake on one occasion ever could.

Often I enjoy imagining my late grandmother’s reaction to conundrums I encounter, including this cake business. I learned to cook from her, a woman whose life was touched by both the Holocaust and the Great Depression. Lil Pachter almost never shopped in bakeries. She might have purchased a cake on occasion, but only if it was on sale—and at a steep discount. My Mema was known as a skilled baker, a reputation she cherished—store-bought was for other, less talented homemakers. As for hostess gifts, she believed that offerings were meant to show affection, and also grandiose generosity. She didn’t bring just one batch of mandel brot when she could bring you three. I can hear her telling Conroy: “Who doesn’t bring the whole cake? What a farkakta thing!” Farkakta loosely translates from the Yiddish as shitty. To me, she would say, “Why do you spend even one minute thinking about half of a cake? Go to work, you have a deadline.”

Addendum: In early March of this year, basketball fans may recall that the Cleveland Cavaliers shooting guard J.R. Smith received a one-game suspension. ESPN reported that his offense occurred during a practice in which, enraged, Smith threw a bowl of soup at his team’s assistant coach. Smith has refused to say what kind of soup, despite the fact that veteran sports writer Tom Withers repeatedly tried to get the answer. “I don’t even remember,” Smith told Withers. I would argue that he most likely does. And that it matters, narratively, to the texture of the events. There’s a difference between, say, gazpacho and bison chili. For that matter, there’s a difference between soup that’s in a china bowl and soup that comes in a paper take-out container. And was there only one slurp left, or a whole cup? Was the soup piping hot or stone cold? Let the reveries begin . . .

This installment of The By and By is curated by the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University (CDS). CDS is dedicated to documentary expression and its role in creating a more just society. A nonprofit affiliate of Duke University, CDS teaches, produces, and presents the documentary arts across a full range of media—photography, audio, film, writing, experimental and new media—for students and audiences of all ages. CDS is renowned for innovative undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education classes; the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival; curated exhibitions; international prizes; award-winning books; radio programs and a podcast; and groundbreaking projects. For more information, visit the CDS website.

Enjoy this story? Read more at The By and By and subscribe to the Oxford American.