The Inscrutable Calvinist

A few years ago, I decided it would be fun to go to a prayer breakfast. Have you heard of these? Everybody’s doing them. Republicans do them because that’s when all their constituents are awake, Democrats because that’s when all theirs are asleep. They have small ones in small towns for Rotarians and large ones in large towns for presidential candidates. I had been invited to other prayer breakfasts in the past, but always declined, leery of any event that sought to put two perfectly fine things together and ruin both, like “Tupperware” and “Party” or “the Captain” and “Tennille.”

The practice appears to have its roots in the Old Testament, when the Israelites were instructed to make a sacrifice every morning, in preparation for the day’s smitings. In the Middle Ages, the practice of predawn prayer was carried on by monkish folk, who prayed for something new to eat besides warm water. And it continues today, where we prostrate ourselves to the Lord God Almighty in close proximity to serving tubs of powdered eggs and sausage patties of such orthodox shape and size they must have been stamped out of a steel press somewhere deep in the Guangdong Province.

I prefer to pray alone, unless I am inside a fiery aircraft with other people. I’m just not very good at it. I try to pray before at least one meal a day, but not in public. My wife knew a family who stood up and held hands and loudly sang the doxology at places like Outback Steakhouse. I love Jesus as much as the next guy, but such a thing would inspire me, I think, to throw a Bloomin' Onion at those people.

Occasionally, I try to pray for sick people and hurt people, but almost never when those prayers are requested on Facebook.

“Prayers comin’ your way!”

“Praying now, girl!”

“Getting my prayer on!”

I don’t know why this bothers me so much, but it doth. It doth a lot. It seems to cheapen the whole act of divine petition. It’s just too personal a thing to be putting out there on what amounts to a digital bridge overpass. I am sorry your cousin’s step-mom’s little teacup poodle has cancer of the face. Really, I am. But I am not going to lift Tiny’s name up in prayer. I don’t even know Tiny. I don’t even know your cousin. I really don’t even know you.

Anne Lamott has famously said that there really are only two prayers: “Thank you, thank you, thank you,” and “Help me, help me, help me.” To that list, I would like to add, “Stop it, stop it, stop it.” And also, “Die, Tiny, die.”

And that is why, ultimately, I decided to attend the Men’s Prayer Breakfast. I needed help. I needed to pray better. I needed to eat many pancakes.

It was a halcyon spring morning as I pulled up to the Savannah Golf Club, the oldest such organization in America, they say, carved out of coastal pastures sometime right after the American Revolution, their muskets beaten into five-irons. Georgia is proud of its Irish blood, but Savannah is animated by the blood of Scots. It is they who brought golf and Calvinism to Savannah. And both, it seems, require very little but patience, as well as a great deal of property.

The breakfast was part of our church’s Missions Conference, an annual event where we bring missionaries from distant pagan lands like Kenya and the University of Georgia to hear harrowing tales of degradation and offer thanksgiving to the Lord for letting us live in Savannah. The theme of the conference was “Declaring the Mystery of Christ,” which seemed odd, as we Presbyterians generally don’t like mystery. We don’t like not knowing things, and we don’t like God not knowing things, which is why we love the idea of predestination.

I walked through the clubhouse and wandered for a bit, a desert pilgrim in the sprawling complex, feeling my way down carpeted hallways and across darkened ballroom dance floors where, in the gloaming, there appeared pictures of happy leprechauns pinned to the wall, in preparation for Savannah’s annual celebration of high blood-alcohol levels. Finally, I heard the delicate murmur of Protestants and joined the body.

The dining room was disappointing. I had been hoping for rich mahoganies—mantles of Georgia granite, pocket doors of rare curly pine, perhaps a roomful of mink-oiled club chairs that once proudly bore the heft of statesmen and generals—but the low-ceilinged hall was suffused in the deadly pallor of fluorescence, with walls of drab eggshell white and the sort of dark green carpet best suited to camouflaging blood and vomit in the hallways of Holiday Inns.

I sat down at an empty table near the front and was soon joined by two or three acquaintances. Everything was very hushed, without even the merest provocation of feelings. Because feelings, as any Calvinist knows, can lead to all sorts of disturbing behaviors, like laughter and eating candy. We are a stoic people. But I was hoping for something different today, I didn’t know what. Joy, perhaps. Enlightenment.

We shuffled the length of the buffet, scooped eggs and hash and ungodly piles of flaccid pork the color of a lung onto heavy industrial china. The place smelled of Sterno.

“Morning.”

“Morning.”

“A lovely spread, this.”

“Quite.”

Everything was so grave. I’d experienced more joy at the burial of a puppy.

We chewed quietly and obediently as speakers slouched toward the podium. They were all good and intelligent people, doctors of divinity, speakers of German, readers of Hebrew, and I was eager to hear their imaginative extrapolations of the glorious inscrutability of Christological mystery. But instead, they spoke like physicians delivering bad news about our moles.

“Speak the mystery of Christ,” Saint Paul says, and “walk in wisdom toward them that are without, redeeming the time.”

I heard no time-redeeming talk. What I heard sounded more like theological dissertations on the Second Law of Thermodynamics and the unwinding spool of the world, this very Calvinist proposition that entropy rules the day and everything is always worse than it was and never as bad as it’s going to be very soon. And also, that we are all extremely, utterly, horribly depraved human beings, all of us. I like the idea of human depravity—really, it explains so much—but it’s not a breakfast-friendly doctrine.

Is this what I’ve come here for? To hear nineteenth-century rhetoricians declaim the world’s depravity from a podium while flanked by vistas of Lowcountry grandeur on a swath of land that cannot be walked except by private invitation? I’d have thought somebody might get up there and at least thank Jesus for inventing the Federal Reserve and economies of scale. I closed my eyes and prayed for salvation.

I wondered, What do black people do at prayer breakfasts? It’d be louder. There'd probably be a band. It would not seem like a puppy had died. This was confirmed later, on the Internet, as I watched what at least one black church prayer breakfast looked like. It looked…well, maybe fun’s not the right word, but lively. All the praying had live musical accompaniment, including a nice little lady tucked into a corner behind an electric piano and a man in a black leather blazer sitting at one of the breakfast tables just like the other diners, except wearing a saxophone. Sometimes he played, sometimes he ate. Another man sang his prayers, which made them more interesting, but not as interesting as the large wooden crucifix that was stuck to his collarbone at an awkward angle, as though it had become lodged in his neck during a hurricane. Sometimes, it was hard to tell what they were praying. At one point, it sounded very much like one lady with a microphone said, “O, God, we ask you to have your baby. O, God, go behind these prison walls today. Oh, touch my nose and bacon.”

It made me wish I had gone to that prayer breakfast. They didn't sound grave at all; heck, they sounded funky.

And then, at our own lily-white breakfast, as the too-sober speaking was over and the praying about to begin, things really did get funky.

The way it started was a minister named Bill came to the podium. Bill (not his name) is a spry old Yank and liable to say anything. He is, for example, the only pastor I’ve ever heard use the phrase rectal procedure in a sermon. He’s that uncle giving the wedding toast who suddenly reaches toward his cat’s fungal infection for an instructive metaphor. But what comes out of his mouth now is no metaphor, but rather an exhortation to kneel.

“The praying shall commence, brothers,” he said, “if everyone could take a knee.”

I was shocked.

Kneeling is supposed to be an affront to good Calvinists, an illicit flirtation of body with spirit. I was raised in a safety-first worship environment: hands to yourself, no sudden movements, no eye contact (also good advice for the castrating of bulls and moving through neighborhoods with possible gang activity). I’d been at this church for a few years and had never seen any proclivity to Popish kneeling. And so it was quite astonishing to see all these joyless Presbyterian men descend to the floor. Before I could even disappear the last plug of sausage from its fatty puddle, the room had emptied as suddenly as a classroom in a tornado drill.

I pushed back my chair as Bill, hiding on the floor behind the lectern, began inviting us to take various prayer assignations. Tom would pray for this, Eddie for that, etc. Voices called out from under the tables, as though trapped under rubble. I sank to the floor, to this unpadded carpet, and wished I had thought to wear more comfortable pants. I had just eaten enough delicious breakfast meat to fill a colonial schooner, and now my khakis conformed to my gut with the dedication of a Danskin leotard.

So there I was, kneeling in my tight pants, eyes closed.

That’s when I remembered about my seasonal vertigo, which causes me to fall over unless my body is lashed to a post. I tried not to open my eyes, but suddenly felt as though the table was rushing to meet my forehead. This would not work, so I grabbed a knee, in the parlance of the football coach, one patella on the floor, one up high. This was a problem, too, because now I found myself in a position not unlike the Archangel Tebow after a successful two-point conversion.

I grabbed the chair next, setting my elbows down on its cushion, hooking my hands into the curlicue struts of its back—a position that was perfectly comfortable, except that it looked as though I was now making love to the furniture.

I’d been to Episcopalian churches where they knelt so much it’d make a man bring a bottle of Dramamine to church; I seemed to remember something about crushed velvet benches. Looking around, though, I saw no benches. The only thing I saw was two or three ancient presbyters who were incapable of kneeling and had thrown themselves prostrate over their plates. I thought some of them might actually be sleeping. I thought one or two might actually be dead.

The praying had long since begun, but I could hear none of it.

In a sudden resignation of will, I settled back into the sitting position commonly known as “Indian-style,” at which point my right kneecap made a sound like a heavy glass paperweight falling onto a concrete floor. I wanted to fall to the floor and scream, but did not. I considered praying for the ability to learn to walk again, but did not.

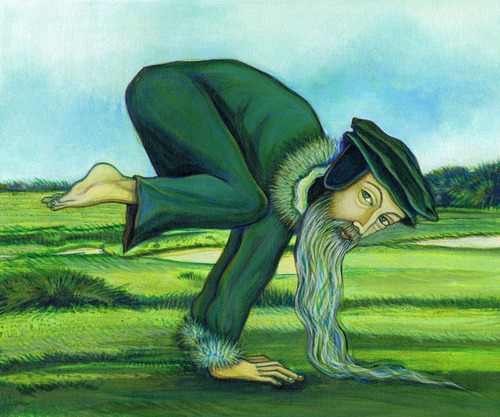

“Getting my prayer on!” 7.5" x 9", acrylic on BFK, Namaste, 2012 (Katherine Sandoz)

Suddenly, I threw myself down into Child’s Pose, a yoga position once practiced in an acting class. For those unfamiliar with the many asanas, this position is better known to physicians as the Fetal Position and among yoga instructors as The Best Position for the Fat People. It almost worked, too, but the pressure on my knee was so great that I catapulted myself onto all fours, like an animal, or one of those women on TV who have their babies on the bathroom floor. O, God, we ask you to have your baby.

I started rocking, praying silently that the praying would end.

“Help me, Jesus,” I said, just like that old woman, rocking, swaying, gently moaning. If anyone had been watching, I am sure I would have been excommunicated.

And then, the praying was over.

We stood, and I pulled myself to an unsteady upright position. Congregations of bones could be heard cracking, returning to their appropriate offices within the body. Boys who had come with their fathers yawned, stretched. The elders, laid across their plates like the victims of stroke, rose from the dead. We barely spoke as we filed out, across the empty country-club dance floor and past the green paper imps on the wall.

Lots of muffled prayers were prayed that morning on that floor, but I heard none of them and am not sure if anyone declared the mystery of Christ, as was promised. The real mystery was these Calvinists, and why Jesus doesn’t just go ahead and smite me now.

I thought of all the sonic waves of all the world’s prayers ricocheting around the planet like a swarm of locusts, uttered up from the mouths of demented peoples who were lying, sitting, kneeling, walking, running, dancing on platforms with crucifixes lodged in their collarbones. I thought some of those prayers were probably necessary, and that really I have had a very good life, and that I am a terrible human being.

But then, any good Calvinist knows that.