PEOPLE WANT TO SEE MOVIES

By Alan Lightman

It began with a death in the family. My Uncle Ed, the most debonair of the clan, a popular guest of the Gentile social clubs despite being Jewish, had succumbed at age ninety-five with a half glass of Johnnie Walker on his bedside table. I came down to Memphis for the funeral.

July 12. Midnight. We sit sweating on Aunt Rosalie’s screened porch beneath a revolving brass fan, the temperature still nearly ninety. For the first time in decades, all the living cousins and nephews and uncles and aunts have been rounded up and thrown together. But only a handful of us remain awake now, dull from the alcohol and the heat, sleepily staring at the curve of lights that wander from the porch through the sweltering gardens to the pool. The sweet smell of honeysuckle floats in the air. Somewhere, in a back room of the house, a Diana Krall song softly plays.

I wipe my moist face with a cocktail napkin, then let my head droop against my chair as I listen to Cousin Lennie hold forth. Now in her mid-eighties, Lennie first scandalized the family in the 1940s when, in the midst of her junior year at Sophie Newcomb, she ran off with a man to Paris. Since then, even during her various marriages, she has occasionally disappeared for weeks at a time.

“Did you know how your grandfather M.A.’s heart attack really happened?” Lennie says to me, smiling slyly and sipping her bourbon. “What do you mean?” “Exertion, bien sur. The best kind. And not with your grandmother.”

Lennie lights a new cigarette and wriggles her stocking covered toes, poised to let fly another story. Cousins nudge forward in their reclining chairs. Someone moans from the pool, the next generation, and Lennie exhales a cool cloud of blue smoke.

The next afternoon, we gather in my grandfather’s old house on Cherry Road, a magical realm of my childhood that remains in the family. Aunt Lila lives here now. From the street, the house appears far smaller than it actually is. Its exterior walls are a copper-colored terra cotta, with beautiful stone accents and a sweeping arched portico adjoining the front door. A gravel drive winds gently through the four-acre wooded property. Over the years, far from the thick air of Memphis, I’ve often walked through this house in my mind—the sun room with its smooth marble floor cool to the bare feet; the dark living room with its antique mahogany commodes from New Orleans and grand piano on which I practiced my scales as a child; the elegant dining room in which my parents and brothers and I and my uncles, aunts, and cousins would sit for the Seder; the damp basement where Hattie Mae, the colored maid, sometimes slept in a small room; the carpeted stairs leading up to mysterious chambers and corridors I wasn’t allowed to see. In the back, behind the gardens of azaleas and boxwoods, was a musty barn converted to a garage, with harnesses and bridles still hung on the walls and the odor of horses. My grandparents kept a mule there named Bob, who carted off the dead leaves in the Fall and returned with compost in the Spring.

The house was built around 1900, when this part of Memphis, ten miles east of Main Street, consisted mostly of farmland. In those days, the big houses were owned by the cotton merchants. People said you could always tell a cotton man by the lint on his trousers. In the 1940s and 1950s, many of the power brokers of Memphis and Nashville—mayors and governors, captains of industry—came to this house to visit my grandfather. In recent years, the neighborhood has been chopped up into half-acre lots with fake Southern mansions crammed side by side. But this modest monument remains. Soon, it too will be gone.

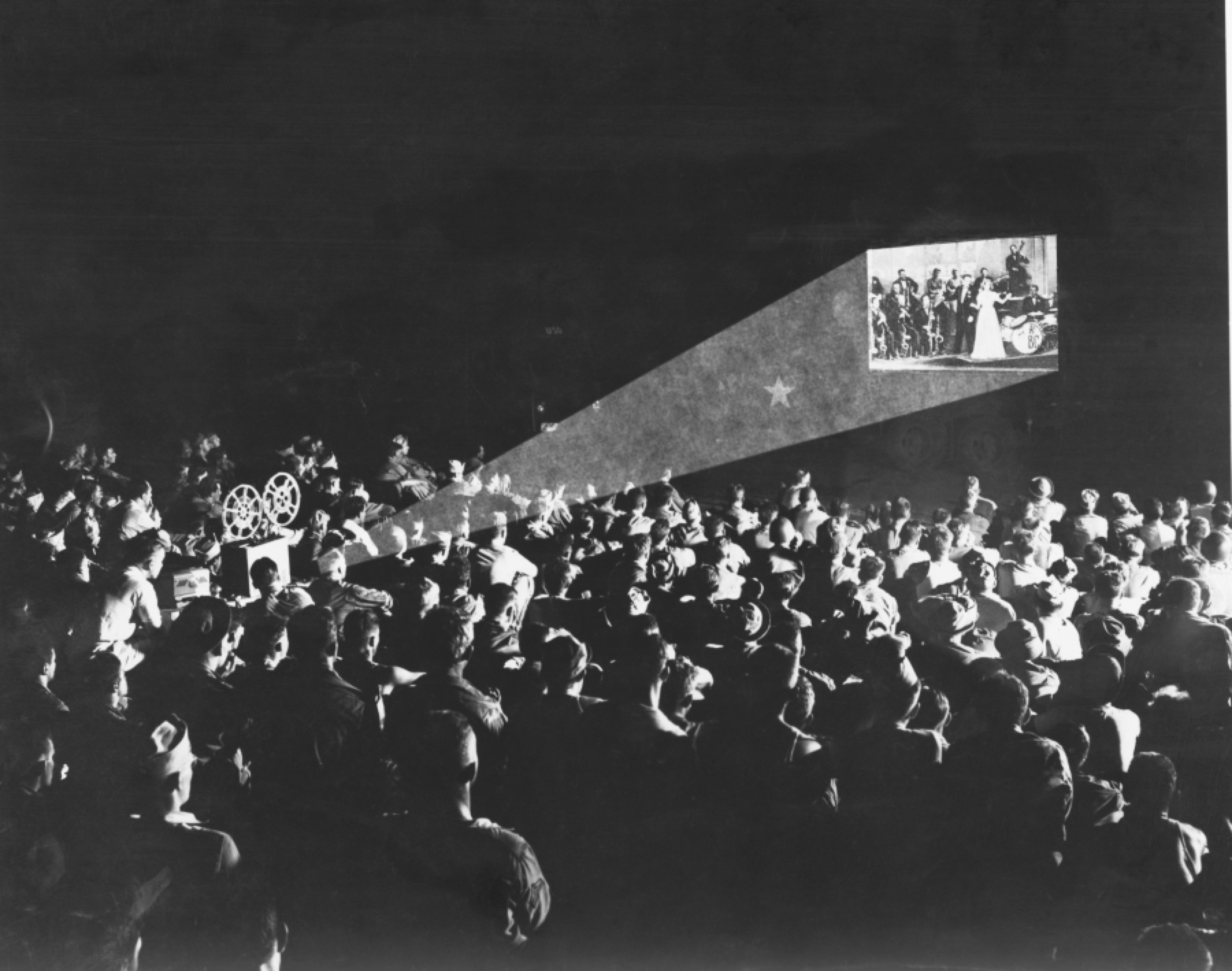

At my insistence, Uncle Harry begins recounting the early days of the family business, the movie business. Every once in a while, Lennie will correct him, they argue for a few moments, and then they compromise on some version of the truth. According to family legend, my father’s father, Maurice Abraham Lightman, known as M.A.—the son of a Hungarian immigrant and trained as a civil engineer—was working on a dam project in Alabama one day in 1915 when he looked out of his hotel window and saw a long line of people waiting to get into a movie theater across the street. In those early days of film, many movie theaters were simply converted storefronts with a projector installed at the back of the room and folding chairs for the audience. M.A., who fancied himself more a showman than an engineer, decided it might be time to try the movie business.

The next year, at the age of twenty-five, M.A. opened his first theater, called The Liberty, in Sheffield, Alabama, where he played the original, silent version of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Some years later, he opened The Majestic in Florence, Alabama, then built the Hillsboro Theater in Nashville. In 1929, he moved his family from Nashville to Memphis and began acquiring and building cinemas not only in Alabama but also in Arkansas, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Missouri. This was the moment when new technology allowed movies to include sound. Over the years, M.A. managed to stay ahead of his competitors on each innovation in motion picture technology and created a movie-house empire of some sixty theaters. Most of my male relatives have worked in the empire: my father, three uncles, an occasional brother or two, several cousins, the children of cousins.

“M. A. wrestled at Vanderbilt, you know,” murmurs Lennie from the couch, where she’s been carefully cradling her head. “When he went into a room, he would ask the biggest man there to lie on the floor, and M.A. would lift him up by his belt. I once saw M.A. do push ups with one arm.” She looks up and stares out into the living room, as if expecting the great man to stride through the arched doorframe. Women worshipped my grandfather. Although I was only ten when he died, I remember him as barrel chested and square-jawed and handsome. He smelled of Old Spice cologne. Although he was probably less than six feet tall, my grandfather seemed far taller. Even photographs of him, from his younger years, convey the physical power and striking good looks that made new acquaintances think he was a movie star. M.A. was the person I wanted to be when I grew up. He was the master of the universe, the undisputed king of the family. It was M.A. who imagined and built the business on which four generations lived. At age forty-three, he swam across the Mississippi. For a number of years, he was president of the national Motion Picture Theater Owners of America. He was founder and president of the Variety Club in Memphis. He was president of the Jewish Welfare Fund. He was president of the Memphis Little Theater and loved to act in plays himself. He was a bridge player of extraordinary cunning and skill. At his peak, in the 1940s, M.A. Lightman ranked among the top bridge players in the world. My father, and various other male family members, withered under his shadow. In fact, I knew very little about my grandfather.

I hear squawking and look up to see a cage of parrots in the little pantry room leading to the kitchen. There have always been parrots in this house. I have dim childhood memories of birds fluttering from lamp shade to lamp shade, sometimes roosting on the teak card table in the corner of the room. At that table, my grandfather played casual bridge games with friends, like a jet plane taxiing for three hours on the runway. I once sat beside him at such a game. After the first round had been played, he turned to me, then eight years old, and loudly announced with perfect accuracy the twelve hidden cards held by each of his two opponents. They didn’t have the heart to continue the game.

Although the sun has slid from the window, the room still blazes with heat. Four of us hold cool iced tea glasses against our faces, as if we were performing some group pantomime in a game of charades.

In mid afternoon, Lennie’s fifth husband, Nate, stops by to pay his respects. Tentatively, he shuffles toward the couch where Lennie slumps in a heap of silk fabric and blonde hair. She looks up, notices him, and waves him away.

Nate is the most Jewish member of the family. Not only was he Bar Mitzvahed. He spent ten years studying the Kabbalah, beyond the call of duty even for an Orthodox Jew. To Lennie’s annoyance, Nate wears a yarmulke every waking hour of the day, seven days a week. Nate will not leave the house without his yarmulke, which he fastens to his bald head with double sided scotch tape. Lennie has been known to hide Nate’s yarmulke in the morning so that she can watch as he searches through every drawer and closet to find it. After ten years, no one in the family can divine why Lennie ever took up with Nate. All of her previous husbands were handsome, while Nate has bulbous eyes that protrude like a bullfrog, sweaty hands, and a bad limp from a car accident in his youth. Still, he has a sweet disposition, and he offers her companionship. And Lennie was no prize herself when she married Nate at age seventy-five. He’s a half decent cook, Lennie says, and he always opens the door for her.

“Have I missed anything?” says Nate, after a few moments of silence.

“We were talking about M.A.” says Uncle Harry.

“Ah, yes,” says Nate.

“And the beginning of the family business.”

“Mysterious circumstances,” says Nate. “Mysterious circumstances.”

“Mysterious to you, my sweet,” says Lennie.

“The facts are the facts.”

The year is 1916. M.A. is burning to buy his first movie theater, but he has no money, nor does his father Papa Joe, unable to collect payments from some derelict clients. “Why in God’s name do you want to own a movie theater?” says Papa Joe in his heavy Hungarian accent. “Do something useful. Aren’t you trained as an engineer? Build roads. Help me in the quarry.” “I want a movie theater,” says M.A.

The next morning, M.A. packs two clean white shirts and a tie in his raggedy college suitcase and takes the train to New York, to visit Papa Joe’s older brother Jacob. Uncle Jacob, childless, has money from his confectionary in the Lower East Side, but he has never shared fifty cents with the rest of the family, and his Gentile wife would rather convert to Judaism than set foot below the Mason-Dixon line.

M.A. has never been to the North before. He has taken road trips in a borrowed Whiting Runabout to Knoxville and Jackson and Memphis, and even as far as Lexington, Kentucky. But New York City is an ocean that has flooded his mind—the tall buildings that punch holes in the sky, the rows upon rows of apartment windows, the scissoring crowds on the streets, the peddlers and shops, the automobiles, the shouts and the blares. He notices everything. He hears the wild thunder of time and the future. After dinner, M.A. outlines his business plan to his uncle and delicately asks for a loan. They sit in the little living room with photographs of railroad stations on the wall, the strong odor of Uncle Jacob’s cigar, the sounds of honking on the street. Nothing doing, says Jacob. M.A. pleads. He is wearing his white shirt and his tie, and he hates asking anybody for anything. Uncle Jacob offers him a glass of port, which M.A. politely declines. All he needs is $1500, he says. He is certain that he will be able to pay back the money within two years, with interest. People want to see movies, says M.A., strong and eager and leaning forward in his chair. I’m sorry, says Jacob. I am not a charity. We have our own expenses, says Jacob’s wife. I am not asking for charity, says M.A. He is standing now, enormous. He fills up the room. He and his uncle exchange unpleasant remarks. You shouldn’t have come, says Jacob, fear in his voice.

Without further words, M.A. takes the train back to Nashville. Two days later, Uncle Jacob is killed by a trolley car while crossing the street.

His will leaves three thousand dollars to M.A.

“M.A. always got what he wanted,” says Nate in a low voice.

“M.A. never talked about that trip to New York,” says Uncle Harry.

“There are strange powers at work in the world,” says Nate.

I can never be sure what Nate knows to be absolutely true and what he embroiders. But my great uncle Jacob was indeed killed by a trolley, at the time M.A. started his empire. And here we all are gathered in M.A.’s old house, sitting in the room where he sat, looking out at the grounds that he kept, living off the business he started, endowed with a slight thickening of our eyelids, like his.

One evening Nate takes me out for a drive, to show me new parts of the city. Unexpectedly, he unveils his theory about the ghost that haunts the Lightman family. “It’s all in the Kabbalah,” says Nate, whispering to me although he and I are the only people in the car. In Kabbalah, the mystical element of Judaism, there is a concept known as gilgul neshamot, which literally means “cycle of souls.” The Kabbalists believe that the spirit of a dead person can inhabit the body of another individual, and then another, forever. When the deceased is a benevolent patriarch of the family and the person inheriting his good soul is a blood descendant, the idea merges with another Hebrew expression, zechut avot, meaning “merit of our fathers.” But when the wandering ghost of the father not only creates further good deeds but also wreaks havoc and destruction, when that ghost can reach out with its shadowy hand over many generations, both visibly and invisibly, when that ghost is so powerful and big that it can control the joys and sorrows and even the destinies of sons and daughters and their sons and daughters like a wind blowing small boats at sea, then the idea has blossomed into some bigger thing without a name. But the phenomenon exists. According to Nate, M.A. Lightman, my grandfather, unleashed a gilgul neshamot and a zechut avot and a dybbuk, an evil spirit, all in one gasp. M.A.’s presence and power did not die with his body fifty years ago, says Nate. For good and for ill, his ghost has haunted my father, my uncles and aunts, me and my brothers and cousins and numerous other Lightman descendants. His ghost has even haunted innocent bystanders like Nate, who tripped into the family by marriage late in life.

Phasma. That’s what Nate and I decide to call the thing. The phasma can spread sideways to brothers and sisters. The phasma does not necessarily obey the usual relations between time and space. It can act during the lifetime of the patriarch, and it can even reach backwards in time to fasten its grip on family members who lived out their days long before the patriarch was born. In other words, the phasma can originate at one tick in time and then creep out from there in both directions of time, future and past. No one can control a phasma. Being aware that a phasma is at work offers no help, and being unaware also offers no help. “It’s a weird, weird thing,” Nate whispers to me as he drives carefully down dark streets. “But then everything is weird. We’ve got a problem, my friend.”

Joseph Patrick Kennedy, the powerful and ruthless patriarch of the Kennedy family, undoubtedly created a phasma. It is easy to see the phasma’s ambitious hand in the shoving of Joseph’s son John to the presidency, although in this case the phasma pulled a trick and first murdered older brother Joe Junior, whom Joseph had been grooming for president. (Which illustrates another point about the phasma: it can deceive and mislead even the patriarch himself.) Not so obvious was the death of John’s son, JFK Jr. After his private plane crashed off Martha’s Vineyard in 1999, the National Transportation Safety Board called the cause of the crash “spatial disorientation.” “Not a chance,” says Nate. “It was the phasma.”

According to Nate, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart created a phasma that sang. The phasma, drunk with Mozart’s genius, stumbled backwards in time to over forty years before Wolfgang was born in order to sing an aria from “Lucio Silla” to his paternal grandmother, Anna Maria Sulzer. Certain documents attest to the fact that one day the girl clearly heard the melody in her head, sixty years before her grandson would write it. But the phasma was not satisfied. The next morning, sixteen-year-old Anna was walking in the woods when she found a box containing a hundred silver thalers, a gift from the phasma that made her ambitious and gracious and that completely changed her life.

“Which all goes to show,” says Nate, as we creep up to a red light at Poplar and Perkins. “Keep your eyes open. You know what I’m saying?”

A week later, I am out again driving with Nate, in his ten-year-old green Honda Civic with a busted fan belt that goes “clap, clap, clap, clap.” He refuses to have it repaired. Lennie drives a late model Cadillac, but Nate prefers his old Civic. “No one talks about how M.A. got to where M.A. got,” says Nate. “The man had a ferocious ambition. Had to. To do everything he did.” Nate looks over at me and whispers, “I know things about M.A. that nobody else in the family knows. Or wants to talk about.” “How do you know?” I ask.

In mid March of 1932, at age forty, M.A. was re-elected president of the Motion Picture Theater Owners of America. Immediately afterwards, the two hundred members and their wives gathered in the grand ballroom of the Willard Hotel, in downtown Washington DC. At this point in his life, M.A. possessed considerably more polish than when he had visited his uncle in New York fifteen years earlier. He had traveled to Chicago, Miami, Philadelphia, and Las Vegas for bridge tournaments, to various other cities for the annual MPTOA conventions, and he been out to Los Angeles to visit the film studios in Hollywood. Malco Theaters Incorporated now owned some forty movie houses in half a dozen states. Film and Radio Review had recently written that “No man in the motion picture industry has made such rapid strides as M.A. Lightman.”

At 6 P.M., showered and shaved and dressed in a grey herringbone suit bought for this occasion, M.A. stood by the west portico window looking out. The grand ballroom of the Willard, at an altitude of twelve stories, had a magnificent view of the city, including the White House only a stone’s throw away. Destroyed by a fire in 1922, the cavern of a room had been completely restored, including its marble columns framing the walls, its white paneled porticos, its extravagant chandeliers, and its ornate ceiling moldings. Unfortunately, his wife Celia could not be there that night. She had planned to come, to help celebrate another of her husband’s victories, but nine-year-old Lila had suddenly been stricken with chicken pox. M.A. was always more comfortable when Celia was by his side. She could talk to anyone about history and art and the affairs of the world.

At 6:30 P.M., “cocktails” were served. This was a cruel joke. Uniformed waiters wearing tuxedo waist sashes walked about with silver trays of Coca Colas and cranberry juice, alcohol being forbidden. The movie men grumbled. Back home, each of them had their illegal speakeasies and personal liquor supplies. “What’s wrong with this country?” said a man from Houston, trailing a young woman in a lavender evening gown and a jeweled cloud of cigarette smoke.

M.A. worked the crowd. “Congratulations.” “Congratulations, M.A.” “Thank you. How’s that boy of yours, the lawyer?” M.A. could name half the theater owners and even some of their children. Several years earlier, he had instructed Fannie, his secretary, to keep a running notebook of the members and their families, and he routinely memorized the book on the long train rides from Memphis to national conventions, just as he could memorize the cards played in a game of bridge. M.A. had two strikes against him. He was a Southerner. And he was a Jew. Despite these disabilities, he was well liked by his peers. He was athletic and could talk sports. He was good looking and smart, but he did not condescend. He was a fierce competitor, but also a straight shooter. M.A. was honest, but he didn’t see any reason to be overly trusting with people, and certainly not business competitors. He had watched his own father work his way up from a dusty stone quarry bought with borrowed money, get beaten down, and rise again, and he knew that behind the smiles of most people were personal ambitions and greed. He accepted that. The world was what it was. He was generous to those of less fortune, quite generous, but he always watched his back.

M.A. would have pulled out his pocket watch and looked at the time, 7:00 P.M. His surprise was two hours away. He dropped the watch back in his suit pocket. The cheap watch had run perfectly for over a decade. Near the end of tedious business meetings, he would take out his watch and place it on the table with a slight tap.

Dinner in half an hour. He knew how these theater owners thought. They liked a good show. And so did he. Some people had already sat down at their numbered tables, and he wandered from table to table saying hello and shaking hands. The air bloomed with the fragrance of roses and gardenias from the ladies’ perfumes. Many of the women were beautiful, M.A. must have noted, and young, and not all of them the recorded mates of their male partners. Their eyes darted about the room.

“You got the scene,” says Nate.

M.A. had a lot of friends at the convention. One of them was a man named Tully Klyce, from Omaha. M.A. would have sat down next to Tully, whose wife had just left him. Tully, a little man with a sympathetic face, leaned close to M.A. “Did anything seem funny about Jane when you saw her last Fall?” he said in a low voice. “I didn’t notice anything,” M.A. whispered back. “Something was going on,” whispered Tully. “You look terrible,” said M.A. “I know,” said Tully. “Call me next week,” said M.A. and he patted his friend on the back. “How’s business in Omaha?” “Not bad,” said Tully. “We’re setting records with Shanghai Express.” “Memphis too,” said M.A. In fact, the movie business was doing well through the Depression—some 60 to 80 million customers per week, according to a recent issue of Variety magazine—and you could see the success in the lamé gowns and diamond necklaces of the women at the tables. The theater owners were not hurting. As people sipped on the cokes, the conversation shifted back and forth between the blockbuster Shanghai Express, released in early February and still playing in theaters nationwide, and the sensational Lindberg kidnapping only two weeks earlier. Now and then, the women left their tables in pairs, to powder their noses in the ladies’ room.

About this time, M.A. would have walked to the south window and gazed out, triumphant. Of course he would have been triumphant. The lights of the city gleamed in the night. He could see the great buildings on the mall and the reflecting pool between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. The future was coming so suddenly, rushing and loud like thunder. And he was riding that thunder, here in the capital of the nation, sometimes called a Southern city, but actually so different from Atlanta and Louisville and Nashville and Memphis, where he had just moved with his family three years ago, bought the copper-colored house on Cherry, bought himself a new Ford Cabriolet with a yellow canvas top and yellow walled tires, had several lunches with young Mayor Overton, who kept asking M.A. to introduce him to movie stars. Memphis was more flamboyant than Nashville. Memphis had the Mississippi River and the riverboats and the barge parties with music, Memphis had Beale Street, Memphis had the Monarch Saloon with its cast-iron store front and the mirrors encircling the lobby and the barricaded gambling room in the back, Memphis had cotton and the new Cotton Carnival, started by his friend Arthur Halle, a week of costumes and dancing and marching bands. And he could do business in Memphis. He had already twice met the warlord of Memphis, Edward Hull Crump, and had received Mr. Crump’s blessing.

At 8:30 P.M., M.A. took the elevator to a room on the tenth floor to check on the arrival of his special guest and to make sure that she and her people were comfortable. The room would have been full of cigarette smoke and half open suitcases. It was a long flight, said one of the agents from Paramount, and no booze. M.A. whispered something in the ear of his special guest, and she smiled at him. He held her hand for a moment, then returned to the ballroom, where dessert was being served.

At 9:00 P.M., M.A. climbed the stairs to the stage and announced that he had brought a surprise for the evening. And out walked Marlene Dietrich, star of Shanghai Express, Paramount’s answer to MGM’s Greta Garbo, dressed in a strapless black gown with silver sequins and black gloves that went half way up her arms but stopped short of her creamy white shoulders. There was a gasp and a moment of silence. Then the house exploded in applause.

“Recorded history,” says Nate, “most of it. And I know the rest from Tully Klyce’s son Martin. But you won’t hear one word of this from Lennie or Lila or your father. No sir.”

In the 1930s and 1940s, M.A. consolidated his empire. He bought out his business partners, so that he was sole owner of Malco Theaters Incorporated. In the evenings, when he wasn’t away travelling on business or bridge tournaments, M.A. would lie on the sofa in the living room, next to the grand piano, and read crime novels. Celia was in charge of reading to the children and caring for them. He loved his children, of course, but after spending a half hour with them, he found himself bored. M.A. would never admit such a thing, even to Celia. His children just weren’t as interesting as the other activities in his life. His bridge games kept his mind sharp, and he craved the high adrenaline national tournaments in the luxury hotels in Chicago and New York. He relished the looks of surprise and defeat in the faces of other players, the best players in the world, when he out maneuvered them in battle. And his movie theaters.

The way M.A. saw it, he was contributing to the mental and spiritual life of the nation. The movies not only entertained people, the movies helped people make sense of their lives, the movies were stories, and people needed stories. The movies sustained people. Many times—and this is well documented—M.A. sat in one of his theaters with the audience and watched customers laugh or cry, and he watched them come out of the theater excited and moved and dreaming new dreams for their lives. In his mind, and maybe in reality, he was an agent of change. He was creating something new from nothing, something from his own hands, something that had never existed before. He, the son of an uneducated Hungarian immigrant. Malco Theaters Incorporated. It would last a century, maybe longer. The generations of human beings, tiny specks in the cosmos, came and went, came and went, but he had made something that would last.

© Alan Lightman. All rights reserved.