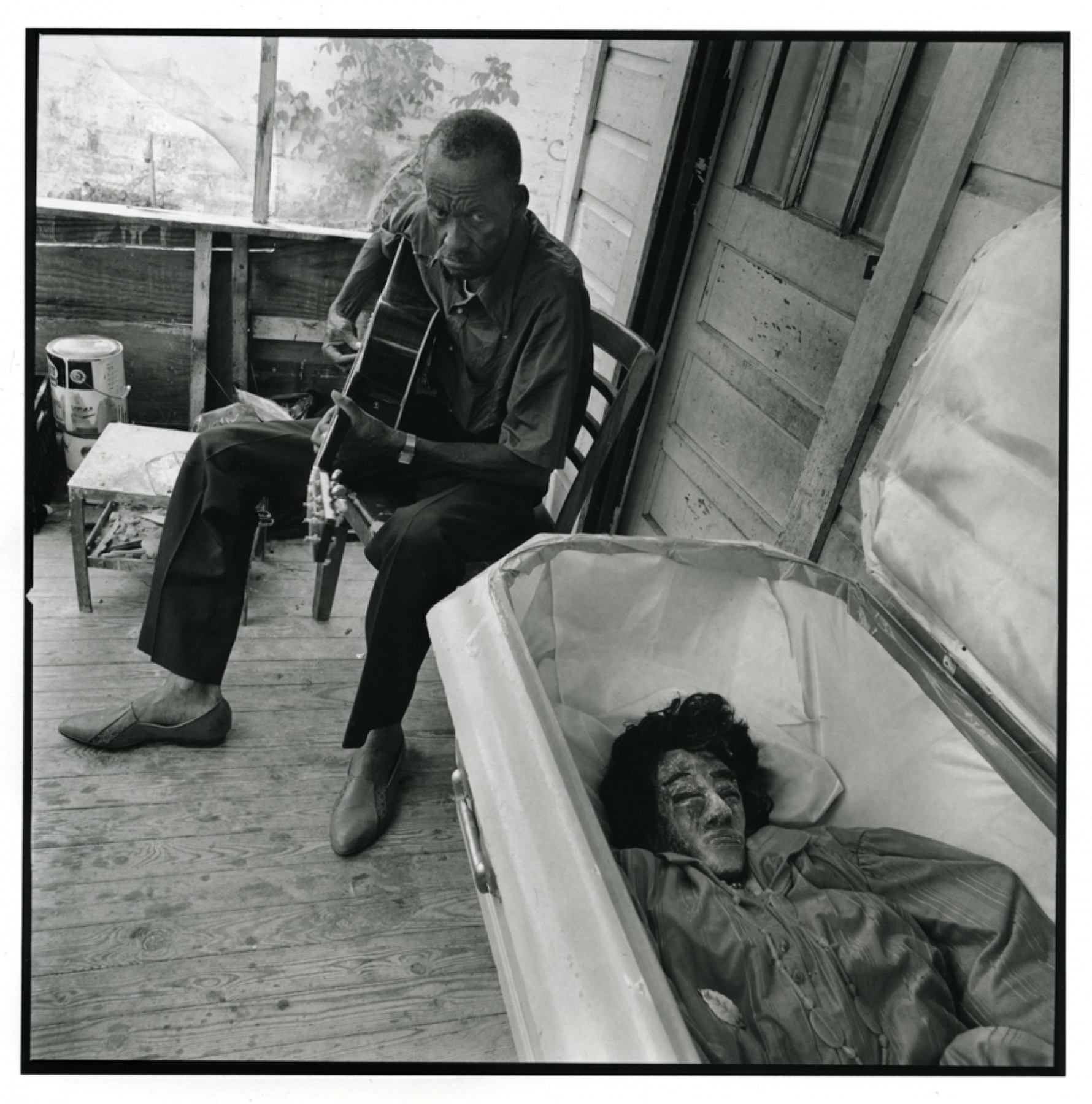

Son Thomas on his porch with his sculpture, Leland, Mississippi, 1989. Photograph by Rex Miller/Rexpix

Son Thomas Makes a Ladyhead

By Cree McCree

Late September, 1989: The Zion Tabernacle Church in Leland, Mississippi, sits directly across from James “Son” Thomas’s house, so that Hutson Street cuts a literal swath between God and the Devil, that old Southern dichotomy. Gospel belongs to God and the blues is the Devil’s business, and here the blues takes the form of Son Thomas, whose spare bottleneck slide strips the tradition down to its roots. Son’s blues run deep into the Delta soil, wrenched from the cotton-field oppression of a past that still hangs heavy over the present. Just last week—while blues fans were gathering in Greenville for the annual Delta Blues Festival—Ole Miss frat boys dumped naked pledges on the historically black Rust College campus as part of an Ole Miss hazing prank. The pledges were painted with racial epithets.

The neighborhood kids on Hutson Street are a little spooked by the baby blue coffin on Son’s porch, and the life-sized clay lady who resides inside. Dressed in go-to-meetin’ finery—a hot pink dress and orange plastic beads—she has sculpted hands folded across her belly, the fingernails painted the same ruby red as her lips.

Son’s been sculpting figures and heads and skulls from clay gathered in the nearby hills for just about as long as he’s been playing the blues, which is to say: all his life. (His first guitar was a Gene Autry, ordered from Sears Roebuck.) He’s particularly fond of skulls embedded with human teeth, like the one that gave his Grandpa the heebie-jeebies when he showed the old man his artwork a half-century ago. Son sells his pieces as fast as he can make them, and he’s got a backlog of orders that will help him pay off his debts. Hospital bills have been piling up since his old lady, now his ex, surprised him with a .22 rifle almost a decade ago. (She shot him in the stomach.) He needs bail money for the son, gone bad on crack, who’s waiting on a trial date over in Greenville. A retread to replace the tire gouged by broken glass on his way home from the Delta Blues Festival. The $125 rent he pays on the railroad flat with a leaky roof he shares with his other son Pat, who’s hard of hearing and picks up whatever shifts he can as a gravedigger at the local cemetery.

Son had intended to spend the last couple of days working clay into life, but that was before his dog, Snow, a white German shepherd he got in a package deal with a used amp for $100, took a nip out of his three-year-old nephew. The kid’s going to be okay, but Son had to lay down $70 in the ER because his niece with the Medicaid card was nowhere to be found. Son’s afraid of what might happen if Snow’s next victim isn’t kinfolk but a neighborhood child. “He’s a good dog, but you can’t trust the breed.”

I’m here to buy a sculpture, a transaction we discussed last week when I came to the house to interview Son for a story on the Delta blues. He waves me up to the porch with a languid lift of an arm bas-reliefed with veins from the long years of sharecropping. “I didn’t think you was comin’ back,” he says. Son was skeptical that I’d return to complete the deal, though I’d sealed the promise with a hug when I left the other day. (“This is the first time I’ve ever been hugged by a white woman,” he’d told me, accepting the embrace somewhat warily. “Except for Nancy Reagan. But she only put her arm around me, so it wasn’t a real hug.”) There’s a photo of Son and Nancy hanging on the wall, taken when his sculptures traveled to Washington, D.C. for a national folk art show. Nancy is beaming her photo-op Samaritan smile, but Son looks rather grim. The shot was taken seven weeks after he took the bullet in his belly, and he was still drinking and having periodic seizures, one of which resulted in third-degree burns on his right hand when he collapsed on an electric heater.

Son is wary of outsiders. Too many white folks have paraded past him, taking his music and his image and his stories and giving nothing in return. But he seems pleased to find my word is good, and he accepts my takeout chicken dinner from Lili Robinson’s Soulfood Cafe, handing it to Pat to “put it up” for later. Then he smiles, the light returning to eyes as deep-set as the hollows of his clay skulls. “I do believe I feel like workin’ now,” he says. “Gonna make me a ladyhead.”

While Pat softens up a batch of the hard hill clay in a washtub, stirring it with his gravedigger’s shovel—“it don’t hold much water so it dries fast”—Son tells me he rarely allows people to watch him work. “Too damn distractin’.” I promise to stay quiet. He nods. “You learn more by keepin’ quiet.”

Son slips a piece of cardboard under a raw lump of coarse mottled clay, then molds it into an oblong shape about the size of a five-pound loaf of bread. Later, he’ll paint the clay a color closer to his own skin tone, but right now it’s yellow-beige, like the skin of a jaundiced white man. A backless chair serves as his work surface, with a tray underneath that holds a clutter of wire, marbles, clippers, and beads. The first tool he reaches for is an empty whiskey pint bottle. He uses this to make the initial cuts that determine the shape of the skull, the shape that “just comes out of the clay.”

With four practiced whacks of the bottle, he carves out the base. Then, with a series of gentle taps, he refines the chin line and neck and makes a rough outline of the nose. “This looks easy but it ain’t,” Son says. It takes years to get it right, to exert just the right amount of pressure without cracking the clay. He works quickly with no wasted motion, smoothing the surface with long, tapered fingers fine-tuned to the hidden bone structure of clay. Using his thumbs, he makes two deep hollows for the eyes, pausing to regard his handiwork. A frown flickers across his face. Then he rises and crosses to another corner of the porch. Rummaging through a box, he plucks out two marbles: “They just feel right.”

Son presses the marbles into the clay sockets, two startled-looking cat’s eyes. “I’m workin’ slow today,” he notes. “What takes time is when you have to keep gettin’ up and down to find things you need.” As if on cue, Pat appears with a cardboard box containing two dozen wigs: afros, wavy and straight styles in a palette of browns and blacks, none of them blonde except for a snarled wiglet.

But Son’s not ready for those yet. As I watch him work, the ladyhead begins to come to life, transforming from what looks like an Etruscan relic into something softer, more sensual. Son dips his fingers into a plastic margarine tub of water and begins to mold the fine features—eyelids, a small, impertinent mouth—from the still-moist clay remaining on his palette. His movements are deft and delicate, almost feminine, in sharp contrast to his bluesman’s hands. When Son plays steel string and slide, his fingers are emphatically masculine in their attack, forging rhythms that cut time with unexpected phrasing much older than the blues that pre-dates the 12-bar format. What bridges the two creative acts is the homing instinct of Son’s fingers.

He reaches into the wig box. I expect him to try several styles on for size, but his hand goes immediately to a short, wavy head of hair. It works. The newly coifed ladyhead looks somewhat androgynous in her short-cropped waves, but the style makes a fine frame for her high, proud cheekbones. Son’s own hair is a fine, grey-flecked stubble, and I ask him if he’s ever tried on samples from his wig collection. “No,” he says with a laugh, “but maybe I should.”

James “Son” Thomas died on June 26, 1993.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.