Esquerita and the Voola

By Baynard Woods

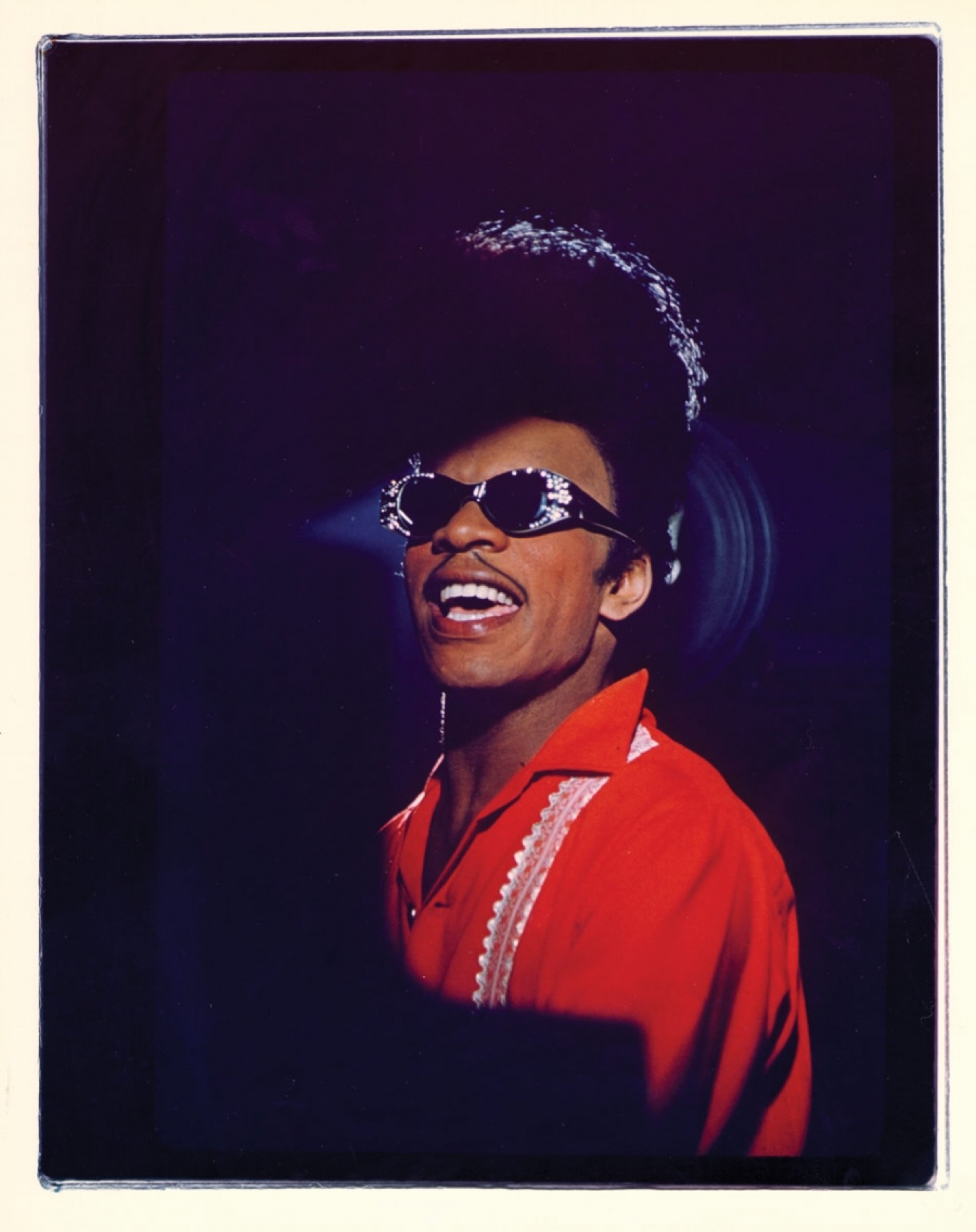

Photo of Esquerita courtesy of Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images

I

n the early 1950s, Richard Penniman, who would soon become famous as Little Richard, liked to sit around an all-night restaurant in the bus station in Macon, Georgia, and watch people come in.

Oh boy!, he thought, when he saw an imposing, six-foot-two figure descend from the bus: It was Eskew Reeder, another gay, Black teenage performer moving between the worlds of the church and the chitlin’ circuit, as the network of African-American performance venues was known.

Reeder was fifteen or so, and he was already traveling the South with a “lady preacher” named Sister Rosa, who was hawking store-bought bread that was supposed to be blessed. As Penniman later told the story, he and Reeder met in the bus station restaurant where Penniman was “trying to catch something—you know, have sex.”

“I thought Esquerita was really crazy about me, you know,” Penniman recalled to Charles White, the author of The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock.

Reeder’s handsome face was punctuated by lips that seemed to be permanently set into the kind of cocked, half-ironic sneer that would come to define a certain kind of rock & roll star, from Elvis Presley to Billy Idol. Penniman had already cut a couple of unnoticed records by then, but Reeder, who would later be known as Esquerita, would that night become Penniman’s teacher.

“Esquerita and me went to my house and he got on the piano and he played ‘One Mint Julep,’” Penniman said. “It sounded so pretty. The bass was fantastic. He had the biggest hands of anybody I’d ever seen. His hands was about the size of two of my hands put together. It sounded great.”

“Hey, how do you do that?” Penniman asked.

“I’ll teach you,” Reeder replied.

“And that’s when I really started playing,” Penniman said.

Penniman figured he met Esquerita in 1951, although musicologists Pierre Monnery and Jay Halsey place the meeting a couple of years later, since “One Mint Julep” wasn’t recorded by the Clovers until 1952. Regardless, it was a night that changed American music. It wasn’t just the way Esquerita pounded out a percussive rhythm with his left hand that impressed Penniman. He overlaid it with the high-and-loose honky-tonk treble plinking that he likely learned from the country songs he loved to hear on the radio.

“He was one of the greatest pianists and that’s including Jerry Lee Lewis, Stevie Wonder, or anybody I’ve ever heard,” Penniman said. “I learned a whole lot about phrasing from him. He really taught me a lot.”

According to Reeder, he also taught Penniman his own signature singing style. “When I met Richard he wasn’t using the obligato voice. Just straight singing,” Reeder told Kicks Magazine in 1983.

Esquerita and Little Richard stayed in touch as friends, collaborators, and rivals until 1986, when Little Richard was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and Esquerita died, a victim of AIDS who was buried in an unmarked grave on Hart Island, New York. Their careers had mirrored each other over rock & roll’s first thirty years, playing out the dualities of the sacred and the profane, music and money, and God and the Voola, what Esquerita called his mojo, the spirit that motivated his music.

Greenville, South Carolina, a city deeply haunted by a vengeful God who seemed to despise rhythm, dancing, homosexuality, and racial mixing above all else, was an unlikely home for Eskew Reeder Jr., who was born there in 1938. Alongside the church, the textile mills were the dominant force in the city—and yet, like the churches, they were a sign of Greenville’s deep segregation. It was not until the 1960s that an African American was hired to do anything other than menial work at a Greenville textile mill.

In 1947, a twenty-four-year-old Black man named Willie Earle was accused of killing a white cab driver in Greenville. He was arrested and held in the county jail until an armada of taxicabs arrived in procession. The drivers removed Earle from the jail. They beat, tortured, and shot him. Thirty-one white men were charged in Earle’s death and several confessed their role in the crime, but the all-white jury found no one guilty.

Rebecca West covered the trial for the New Yorker. To demonstrate the city’s approximation of high culture and its distance from what readers might imagine as a community of hicks, she described the white First Baptist Church downtown in terms of European high art. “In there, on Sunday evenings, there is opera,” West wrote. “[U]ndistracted by the heat, they listen, still and yet soaring, to the anthems sung by an ecstatic choir and to a sermon that is like a bass recitative, ending in an aria of faith, mounting to cadenzas of adoration. In no other place are Baptists likely to remind a stranger of Verdi.”

My grandparents grew up in Greenville mill villages and attended the white First Baptist Church for most of their lives. I was often dragged along, uncomfortable in a starchy Sunday shirt. Unless there had been a great diminution in musical ability, West was overreaching by a long shot.

But back in the ’40s, across town, in the West End neighborhood then known as Greasy Corner, a five-year-old Eskew Reeder Jr. was learning about opera from his neighbors, two sisters named Cleo and Virginia Willis, whose mother taught Reeder to play the piano. “I’d hear those girls doin’ all this and I said ‘Damn, I gotta sing like that too!’” Reeder later recalled.

In 1947, he started playing publicly in the Black Tabernacle Baptist Church, where his mother was choir director. A few years later, he dropped out of school, pursuing a career as a gospel pianist. While white fundamentalists like Bob Jones preached against music, the Black gospel tradition was vital, even wild, as the lines between the secular and the sacred grew ever more fluid, with performers oscillating between the churches they were raised in and the vaudeville shows where they could earn a living.

According to Monnery and Halsey, Reeder played with Sister O. M. Terrell, whose propulsive bass-driven blues guitar technique and gospel shouting surely influenced his performance style. Reeder also performed with the wildly inventive and charismatic gospel howler Brother Joe May, whose music and stage show were essentially proto–rock & roll with religious lyrics—Chuck Berry in the church. Between Terrell and May, Reeder had a blueprint for a new music. And with the makeup tips he and Penniman traded and the pompadour hairstyle both men took from jump blues singer Billy Wright, he had a look to go along with it.

He continued on the gospel circuit for a couple of years, recording with the Heavenly Echoes in Brooklyn, in 1955, when he was eighteen years old. That same year, Penniman, now recording as Little Richard, shook the world with “Tutti Frutti.” The song was something of a fluke. Penniman’s Specialty Records recording session in New Orleans wasn’t going very well, so he went over to the Dew Drop Inn to take a break. Penniman, who had performed in drag as part of various minstrel shows, sat down at the piano and sang a bawdy song he’d been honing on the chitlin’ circuit. The original lyrics were: “Tutti Frutti, good booty . . . if it’s tight, it’s all right / if it’s greasy, it makes it easy.” The wild, driving rhythm and spontaneous singing and falsetto swoops—the stuff that Penniman had learned from Reeder—were exactly what Specialty was looking for. They cleaned up the lyrics and released the song in 1955. “Tutti Frutti” went to No. 2 on the r&b charts. The next year, Penniman’s “Long Tall Sally” reached No. 1. Little Richard was a superstar.

“I think Little Richard copied off him a lot, but Little Richard got to the studio first,” Lightin’ Lee, a New Orleans guitar player who knew both men, recently told me.

Little Richard’s success was both an opportunity and a challenge for Reeder, who could see that he would likely always be considered a Little Richard imitator.

“I had to figure on something I could do that was different, something that would identify me. I knew, with that done, I could sell myself and make a bunch of money,” Reeder said late in his life.

So Reeder did a strange thing for an aspiring rock & roller. He left New York and returned to Greenville.

“I love Greenville, too,” he said. “That’s where Esquerita was created.”

With “Tutti Frutti,” Little Richard had mainstreamed the underground queer Black culture of the South for white kids all around the country.

“It was as if a Martian had landed,” filmmaker John Waters wrote about the first time he put on a Little Richard record, in 1957. “My parents looked stunned. In one magical moment, every fear of my white family had been laid bare: an uninvited, screaming, flamboyant black man was in the living room.”

The new rock & roll music was inherently integrated and interracial. But in Greenville, far more than in Waters’s Baltimore, this music represented the devil and gave the white establishment one more reason to support segregation. Bob Jones University, which had relocated to Greenville in 1947, was increasing its power and influence over all aspects of the city’s political life, and Bob Jones Sr., the school’s founder, argued that segregation was scriptural. “If you are against segregation and against racial separation, then you are against God Almighty,” he said in a radio address that was later printed and widely distributed.

“There is no race trouble here,” Greenville’s mayor Kenneth Cass told Life magazine in 1956. “And there won’t be, unless an agitator comes in and stirs it up.”

Reeder was not the kind of agitator the mayor had in mind, but he must have cut quite a figure strutting around the sepia-toned town in his sequins, rhinestones, and capes. “Black Flash Gordon Rocket ’58,” as Clash member Mick Jones said of him in the Big Audio Dynamite song “Esquerita.”

“I got shit all the time,” Reeder said of townfolks’ reaction to his look. He described a time in Dallas when “this white woman done fainted” when she saw him.

Reeder began playing at the Owl Club, on Washington Street, one of the main drags in the Greasy Corner section of town, which he described later as “a roadhouse—beer, whiskey, bandstand.” He said that he went to the club to book himself a show and the owner was so impressed, he bought a new piano and drum set for the act. “The whole thing at the Owl Club was my look,” Esquerita said. “It’s what made the man buy the drums, buy the piano, this whole thing for me to deal with it. I was so way out at the time!”

For the show, he went by the name “Professor Eskew Reeder.” In the single photograph I’ve been able to find that portrays him in Greenville, he looks majestic behind the piano, wearing white pants and a black jacket with long tails, pounding the keys, and hollering into the microphone. His pompadour is swept forward in a baroque tidal wave that towers above his head, and his face is covered in thick, white pancake makeup, almost as if he was mocking minstrel show blackface.

The Owl Club was open to white patrons, and, in 1958, Paul Peek, a member of Gene Vincent’s rockabilly band the Blue Caps, stopped in and saw Professor Reeder. It was an opportune moment. Specialty had just released “Good Golly, Miss Molly,” a huge hit. Little Richard was one of the biggest stars in the world—but he had quit music and enrolled in a theological college in Alabama.

“If you want to live with the Lord, you can’t rock & roll too. God doesn’t like it,” he told the audience of what he said would be his final show, in 1957.

Little Richard was touring with the Blue Caps when God told him to quit showbiz. All of his spectacular outfits fell to Vincent, who loved Little Richard’s act. So when Peek saw Reeder, he thought the piano player might be able to fill the void left by Little Richard’s conversion. Vincent gave Penniman’s wardrobe to Reeder, and Reeder settled on the multilingual, gender-bending form of his name, which, according to music scholar W. T. Lhamon Jr., was a pun on “esquire-ita” and “esquire-eater” and “excreter”: Esquerita.

In 1958, Capitol released Esquerita’s first singles, including “Esquerita and the Voola,” the artist’s most dissonant song, which begins with a rolling rhumba drumbeat and then takes off into a piano rumble that swerves between the almost-off-the-rails high-note plinking of Thelonious Monk and the raucous bass thudding of Fats Domino. The piano is enough to make “Esquerita and the Voola” one of the most experimental of the early rock singles, but then the wordless vocals come in and things really get weird, as Esquerita executes the kind of operatic howls that others call rock shouting and he called obligato.

Given the outrageous aura surrounding the sequined Esquerita, the executives would have likely seen “Esquerita and the Voola” as a novelty number. Billy Delle, an Esquerita fan and beloved DJ at WWOZ in New Orleans, described the song as “raw jungle music” and exclaimed, with more than a little colonialist exoticism, “Man, you had to look behind you to see if anybody was coming chucking spears at you!”

With its thundering piano and obligato holler, “Esquerita and the Voola” could be read as a response to Little Richard’s conversion. Just as Richard gave himself to the Lord, Esquerita had dedicated his life to the Voola.

The song was ultimately not included on the 1959 Capitol album Esquerita!, which, despite its more conventional rock & roll lyrics, was still far stranger than what the record-buying public was ready for. On the back cover, the label bragged that it was “truly the farthest out man has ever gone.”

“Esquerita played piano with a speed and staccato attack that echoed Little Richard’s style, but the overall sound here in some way conjured a chaotic symphony, as a succession of chords chased each other desperately up the keyboard,” DJ and musicologist Charlie Gillett observed in his book The Sound of the City. “The violence that was normally only a promise (or threat) in rock ‘n’ roll was realized in Esquerita’s sound.”

The album did not sell well. (Gillett went on to write that “there was little sign that anyone responsible for the records had been concerned for their commercial potential.”) Not a single song on Esquerita! ever cracked the charts and soon enough, Capitol dropped Reeder from its roster. From that point on, Reeder drifted around the fringes of the musical world, changing his name almost as often as his address, performing as the Magnificent Malochi, Estrelita, Eskew Reeder, and the Voola.

For a while he lived in Dallas, where he put together a band and recorded a series of demos that were even rawer than the sides he cut for Capitol. From there, he went to New Orleans, where he hung out at the Dew Drop Inn and performed with many of the city’s best musicians.

“So Lloyd [Price] met me in Greenville, Fats met me in Greenville, so when I got down to New Orleans, it was like I was from New Orleans,” Reeder said. “I love it down there.”

Lightin’ Lee remembered seeing him walking around town with “a sway and a swagger.”

“He used to walk up and down the street and he always had girls following him,” Lee said. “He wore makeup, and all kind of perfume. You’d say, ‘Oh, he smell so good.’ What the fuck he got on?”

Esquerita was part of an ensemble that Berry Gordy brought to Detroit in search of a new Motown sound. “We called Berry Gordy and he sent us money to come up. That’s when the Gordy sound changed,” Reeder said later. “We just started jammin’, payin’ no mind, carryin’ on, and Berry taped us right there in Hitsville, USA.”

Motown may have transitioned from a cha-cha rhythm to a harder-charging r&b beat after listening to the crew from New Orleans—other sources back the story up—but there were no hits, or even a record deal, in it for Esquerita.

In the late ’60s, he was back in New York, where he made some of the most astounding music of his career with the great drummer Idris Muhammad, who had recently converted to Islam and was making a transition from r&b and soul to jazz. The songs Esquerita and Muhammad cut were not released at the time, but Esquerita ended up on wax once more as he played backup for Little Richard, who had come back to rock & roll, along with Jimi Hendrix, who was also serving as a sideman. In 1969, Esquerita wrote “Dew Drop Inn,” about the New Orleans club, and Little Richard recorded it, along with another Esquerita number called “Freedom Blues.”

But for the next dozen or so years, Esquerita sunk further into obscurity. He later said that at some point he was living in Puerto Rico, where he went to prison and lost an eye in a fight.

In 1983, a group of white hipster aficionados of early rock & roll and outsider music saw an ad announcing that Esquerita was playing at a small New York City bar called Tramps.

“We knew the Capitol album and the 45s,” Miriam Linna, who had been electrified by the lost history embodied in those records, recently told me. “Where was he all this time?” she wondered.

So Linna and her crew showed up at Tramps—and there he was. “His hair was short, and he looked like he’d ridden some hard miles, but it was he, the guy who made those insane records way back when,” Jim Marshall recalled in a blog for his long-running radio show. “He was amazed and thrilled that anyone, never mind [a] bunch of white kids who were either in diapers or hadn’t been born yet, knew of his great achievements at Capitol Records.”

The group of fans was small but influential. Linna was one of the founders of punk band the Cramps. She and her partner, Billy Miller, had started Kicks, a magazine devoted to lost rock & rollers, outsider musicians, and garage rock. They featured Esquerita on the cover of their third issue.

“I hung around with him a lot and there was always crazy shit happening,” Miller told an interviewer in 2006. “Lunch with Reverend Al Sharpton where both those guys got into an argument over who knew James Brown better, a fistfight on 8th Avenue with Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, a combination of the Lyres and A-Bones backing him at a basement party.”

When Linna brought a gay friend to see an Esquerita soundcheck, the friend said, “Oh my god, that’s Fabulash,” whom he described as “one of the most vicious drag queens that he ever met . . . a really, really overpowering entity.”

Even in this late period, Reeder’s identities and sobriquets continued to morph and multiply.

Around the same time that Linna and Miller started Norton Records to release an album by West Virginia wild man Hasil Adkins, Esquerita got ahold of the masters of some of his unreleased demos and they all agreed Norton would release them.

The last time Esquerita called Linna and Miller (who died in 2016), he got their answering machine, which he, inexplicably, called an “arcocon.” The outgoing message played a snippet of a Little Richard song.

“Billy, Miriam, why you got Richard on your arcocon?” Esquerita said. “I’m at the hospital, bring me some rice and beans. Rice and beans.”

He didn’t say what hospital he was at or why. But another of Linna’s gay friends told her to check Harlem Hospital, where people with a new kind of illness that was devastating the city’s gay community were being treated.

“I called there. I didn’t think anything was going to come of it, but I called and I left a message and they called back and said, ‘Yes, your friend was here and he’s passed away,’” Linna recalled. “And it was such a shock. It was really such a shock.”

Esquerita died in New York City on October 23, 1986, one of the 2,710 people in New York to die of AIDS that year. “Part of the history of the AIDS epidemic is buried on Hart Island,” Melinda Hunt, an activist who has fought to make records about the island public, told the New York Times. “And it’s the unknown part.” Esquerita is buried there in an unmarked grave.

The year after Reeder died, Norton released The Vintage Voola.

In November 1986, a month after Esquerita died, my family moved from South Carolina’s capital city of Columbia to Greenville to live in my grandparents’ basement. We had lost our house when my dad lost his job at an insurance company, and my mom started to support the family by working in her father’s carpet store.

For a fourteen-year-old punk rocker, it was a devastating relocation. It’s not like Columbia was a center of culture, but compared to Greenville, it seemed golden. By the mid-’80s, Greenville was a drab and dreary mill town whose largely empty streets had been left derelict by the early stages of a globalism that no longer needed an army of American millworkers to manufacture its textiles. Left behind was a broken city controlled by Bob Jones University. There was no sign of the Voola anywhere.

Over the next four years, as I grew my hair long, I was regularly pulled over and called a “fag” by Greenville County Sheriff’s deputies, whose black and silver cars inspired terror in me after my first two arrests for weed. Because I was straight, white, and middle class, those arrests did not ruin my life or result in prison time, but I knew I had to escape. In 1992, thirty-four years after Reeder picked up and left Greenville for what seems to have been the final time, I discovered Norton’s The Vintage Voola. For a few moments, I saw the city that I hated so deeply in a different light. It could not be all bad if it had produced the man who made this music. But it also increased my resolve. Like Esquerita, I needed to get out of Greenville.

I never reconciled myself with Greenville. After I left in 1992, I returned only for occasional family visits. But I became obsessed with Esquerita, infected by the Voola, and I was always especially thrilled to tell another former Greenvillian about the miracle our erstwhile city had produced—as if we were all redeemed by his music.

With Norton Records, Linna and Miller continued to champion the legacy of Esquerita. They had assumed that the message on the answering machine would be the last communication they got from the singer. Then, fifteen years later, in what Linna calls a “late night internet miracle,” she discovered on eBay the acetates of the “Sinner Man” sessions that Reeder had recorded with Idris Muhammad. Norton bought them and, in 2012, released Sinner Man: The Lost Session.

The record is built around a long and febrile reimagining of Nina Simone’s “Sinnerman,” with Esquerita playing the organ with one hand and the piano with the other. Its overall intensity and playing are the closest Esquerita came to the wild freedom of “Esquerita and the Voola,” while returning in some ways to his religious roots, as if finally reconciling the two.

As I listened to the song, I recalled Lightnin’ Lee telling me how Esquerita would often play until you’d expect a solo, “and then he’d start preaching, like was telling a story.” That’s what happens in “Sinner Man,” as he informs listeners that they’re in a revival meeting.

The record was released in the same year that several states voted to legalize gay marriage and the nation re-elected our first Black president. There was something in the fierce exhortation of Esquerita and Muhammad that we needed to hear—that Greenville needed to hear. It brought the Voola to the city in the religious language it understood.

But I hear something else in the song, a lament almost, as Esquerita seems to chide the very music he helped create for failing to recognize him.

“What’s the matter with you, rock?” he wails. “Don’t you know I made you?”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.