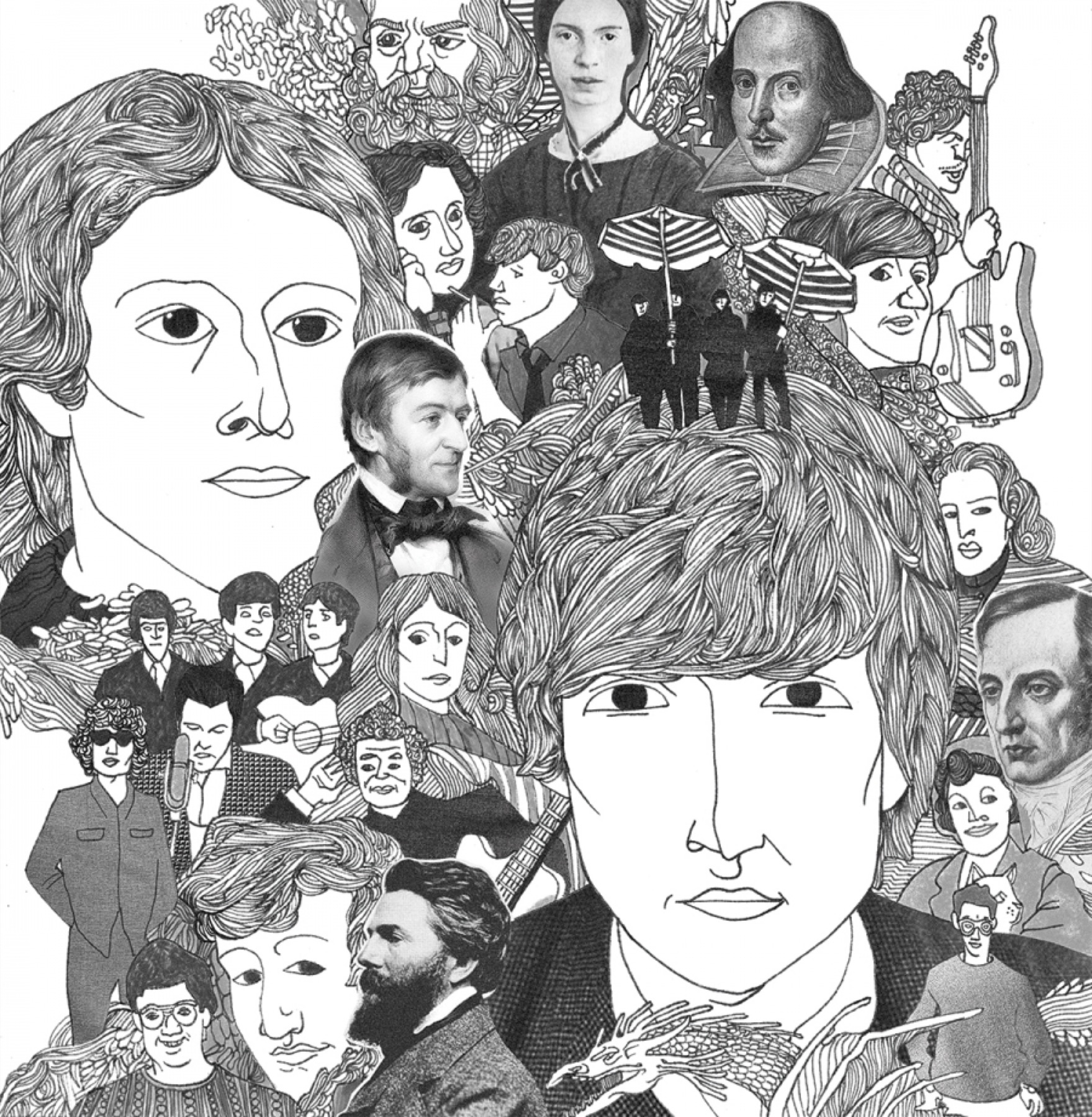

Illustration by Derrick Dent

Meet the Keatles

By David Barbe

1. Gleanings

What struck this particular fifteen-year-old, right off the bat, was the profusion. How could one band have written all these wondrous and varied songs, songs that seemed to have been long embedded in the subconscious, songs that immediately demanded multiple relistenings to glean their joyous intricacies? The year was 1975 and I did not yet understand that by undergoing that rite of discovery and obsession I was living out a cliché. In fact, I might not have been, not yet, or at least I was on the front lines of cliché, since I was among the first generation to discover the Beatles, not piecemeal as the records came out, but whole, the work complete, a trove, a treasure chest for me to open.

Four years later it was 1979 and I was in college. In another year John Lennon would be shot and the Beatles would reenter my consciousness, but at that point I barely thought of them. Maybe I would listen to the second side of Abbey Road once in a while, but I was more interested in Elvis Costello, Neil Young, and a new guy from Jersey who sang about cars. Every Friday afternoon my five roommates and I opened all the windows of our third-floor suite and blasted music that shook the dorm, playing brooms or tennis rackets while singing into hairbrush microphones. I was a bad student, or at least I did not work hard at my required courses, more concerned with listening to music and drawing political cartoons than with school, but there was one class that sparked my imagination. Every Monday and Wednesday I sat in Emerson Hall and listened to a wise, rubber-faced man talk about the pivotal period in English literature, beginning in the mid- to late 1700s, when the tight rules of Neoclassicism gradually loosened into something new, something that would eventually be called Romanticism. The professor's name was Walter Jackson Bate and he spoke of literature as if it were an arena for the heroic. I was particularly excited by his description of the life of John Keats, the famed English poet who died when he was just twenty-five. How could Keats have produced so much poetry, particularly the great odes, in such a short time? This class provided me with the single A of my college career. At the end of the term, I learned that Bate had written a biography of Keats. I bought the book and swallowed it up over winter break.

I have no doubt that the reason I am a writer, that the reason I am typing these words today, is in part because I happened to take Bate's class. Idolatry has its uses, and for the next few years I worshipped Bate while simultaneously combing his biographies of Keats and Samuel Johnson for hints on how I might become an immortal writer too. It is easy to look back on that time and laugh, but without a certain degree of obsession would we ever have the nerve and energy to create art? To make the attempt? Obviously a different kind of idolatry played out, as it never had before in human history, in the life of the young John Lennon and his bandmates. But before John was idolized, he had to do some idolizing himself. Before there was Beatlemania there was Chuck Berry-mania, at least in John Lennon's bedroom. There the fifteen-year-old turned his radio dial as if cracking a safe, trying to capture the signal beaming from Radio Luxembourg in Central Europe, a signal that emerged from the tiny speakers as something that, to his ears, sounded both thrilling and entirely new.

Many years removed from these events, it is no surprise to us that idolatry can turn dark. John Keats, the most indefatigably hopeful of authors, understandably lost hope after he received his early death sentence of tuberculosis. For a while, exhausted and bitter, he swore off books and looked back in embarrassment at the night he put a laurel wreath on his head at the home of the poet Leigh Hunt, laughing at what now seemed his preposterous dream of literary glory. But Keats, being Keats, regained some of his hope and gathered books around him again on his deathbed in Rome in February of 1821.

At the same time that I was first devouring these details about the life of Keats, a man one year older than me, Mark David Chapman, was following in the footsteps of his idol by marrying a Japanese woman several years his senior. Like me, like so many of us, Chapman had experienced his Beatles awakening a few years earlier, in his mid-teens, and for the socially maladjusted youngster the Beatles' music was, according to Philip Norman, a recent biographer of John Lennon, the "main solace for the joylessness of his life." Teenage discomfort pushes some toward creating art, but others respond differently. Ernest Becker once described the neurotic as an "artist manqué," an artist with internal symbols that don't correspond to the world outside. When Chapman flew to New York on December 5, 1980, he was toting fourteen hours of Beatles tapes, and when he approached the Dakota at 10:30 p.m. on December 8th, he was clutching a signed copy of the newly released Double Fantasy album along with a .38 revolver.

At 11:07 that night John Lennon was pronounced dead. I learned the news from a distraught Bill Doyle, my former roommate, the guy who played lead tennis racket during those Friday afternoon concerts. Two nights later Bill and I and a few of our old roommates drove down to Providence, Rhode Island, to watch Bruce Springsteen, who turned down the house lights and dedicated the song "Point Blank" to Lennon's memory.

Lennon died at the relatively advanced age of forty. Chapman was twenty-five when he pulled the trigger.

2. Rubber Mind

I took other courses with Walter Jackson Bate during college, and even met with him once for office hours, though I was too nervous to be particularly coherent. I suppose I would have hung a poster of him in my dorm room if one had existed. It was during those days that I developed the idea of becoming a writer, a great writer, though my sum total of pages written during college was zero.

Lennon died during my sophomore year. Since I was on the traditional timetable, college for me lasted four years. Taking four years as a random slice of time, and applying it to the lives of our two Johns, Keats and Lennon, we make some fairly extraordinary discoveries. During the most productive four-year spans of each man's legendarily productive careers, they achieved things next to which others in their fields will always be judged. Since Keats started writing late, the time span of an undergrad's college life is just about the entire span of his writing career. From 1816 to 1820, he wrote and published his first volume of poems, wrote the four-thousand-line Endymion, and created Hyperion, the majestic fragment that, in Bate's estimation, is the best Miltonic verse "since Milton." He also wrote the great odes, including "Ode to a Nightingale" and "Ode on a Grecian Urn," and finished his last works, Lamia and The Fall of Hyperion. In the course of this period he transformed himself from a beginning poet, capable of diffuse, awkward, and just plain goofy phrases, to a writer of the most brilliant condensed lyric "since Shakespeare." As for Lennon, by stretching the four-year timetable only slightly, we can cover the ground between the U.S. release of Meet the Beatles in January 1964 to that of the White Album in November 1968. Or if we choose, we can bump the time frame forward slightly, and consider the four years from the true breakout album,Rubber Soul, in December 1965, right through the release of Abbey Road in 1969. Either way, this is a stretch of time when the band was releasing two or sometimes three albums a year, all crammed full of original songs, many dashed off and some created under pressure right in the studio; a body of work that, it would not be too much of an exaggeration to say, rivals the work of all other contemporary pop artists combined. Keats, of course, did not have a collaborator, a Paul to his John, and the very best Beatles music usually plays the two men off each other, or with each other, in at least minor ways. But the schism between the two occurred even earlier than we usually think, while the prolific outpouring barely slowed. There were nights when John wrote a dozen songs and there was a sense, during those years, that the songs were gushing forth.

We are naturally thrilled by the spectacle of wild fecundity. In his biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Mind on Fire, Robert Richardson, himself a former student and follower of Bate, writes of a particularly exciting period in Emerson's life: "Emerson was now living as intensely as he ever would; his expressive channels were all wide open. His soaring moods—all constellated around the central perception that every day is both the day of creation and the day of judgment—found form in parables, poems, and dreams." All the channels were wide open! To any creator, this sounds like heaven.

And so the burning question: How did they do it? How did Keats and Lennon create at an unmatched rate and quality? We all might naturally ask these questions, though artists, writers, and musicians can be forgiven if they ask them with a certain greedy, eager need. What chemicals must come together to create this sort of explosion? And can we try it at home?

At first the question seems impossible to answer, since so many of the larger forces in the equation are beyond individual control. For starters, we need to think not in terms of years or days, but centuries. Is it crazy to see parallels between the beginnings of English Romanticism and the birth of rock & roll? It wasn't to my eighteen-year-old mind. "Art proceeds in cycles of freedom and discipline." Walter Jackson Bate was fond of repeating this idea from Alfred North Whitehead, his idol. In the story Bate told during class, 17th- and early 18th-century Neoclassicism, with its emphasis on rules, decorum, formal unity, and discipline, set the stage for what was to come a hundred years later: the breaking out of a kind of exhilarated freedom in the romanticism of Wordsworth, Shelley, Coleridge, and Keats, art that celebrated the spontaneous, the intimate, the local, the (relatively) gritty, the experimental. In short, Neoclassicism was uptight; Neoclassicism was 1950s pop. And Romanticism? Romanticism, of course, was rock & roll.

But to get from old to new we need help. Ushers, even midwives, are required. That is why Bate's course was not called "The Age of Keats" but "The Age of Johnson." Writing in the late 1700s, Samuel Johnson, rhinocerine, traditional, bristling with hard-earned common sense, wasn't exactly Chuck Berry or Elvis. But he was, it turned out, a bridge. He may not have run free but, almost despite himself, he began the process of unlatching the gate so the horse could break out of the barn. And once the horse broke out, you could only watch it go. Rebellion, it turns out, is remarkable fuel for creating. Think of Emerson again, who rode the Romantic wave on this side of the Atlantic and heralded the rebellious gang that followed him, a gang that included Thoreau, Dickinson, Melville, and Whitman. Think of another miraculously creative four-year stretch, from 1851 to 1855, when Emerson was still writing essays and Emily Dickinson had begun to write her poems, and which saw the publication of Whitman's Leaves of Grass, Thoreau'sWalden, and Melville's Moby-Dick.

So there were larger historical currents that young John Lennon, for instance, growing up with Aunt Mimi in their Liverpool flat, skipping school, learning harmonica then guitar, listening to radio at night, sneaking smokes with friends, knew little of. Then there were the smaller tricks of fate. If John were born two years earlier there would have been no Radio Luxembourg to listen to in his bedroom; if he were born two years later, he would have missed the wave. And there is no other word than fateful to describe July 6, 1957, the day he happened to meet the outgoing fifteen-year-old showman with the free-ranging voice named Paul McCartney, just at the moment he was growing dissatisfied with the limits of his own band, the Quarrymen.

Artists don't like to dwell on the idea of fate; it makes them understandably uneasy. And of course no one likes to dwell on the story of the various Beatles drummers. Is there a more unpleasant tale in the history of musical careers (and careerism) than that of Peter Best, kicked out of the band, by then called the Beatles, just as they signed their first record deal and were poised to take over the world? Best was the nicest-looking and most popular Beatle and he didn't see it coming when a ruthless John Lennon, aided by an equally ruthless but smiling Paul McCartney, lowered the boom. He didn't know, for all the pain he felt at that moment, that he would be doomed to one of history's most appalling cases of What if? Conversely, Richard Starkey's early life reads like a Dickens tale, the little boy deserted by his father, falling into comas and living in and out of sick homes, and so it seems miraculous, the stuff of the most absurd Hollywood drama, that he ever became Ringo, "the luckiest man alive."

The early life of John Keats could be ripped from the pages of Dickens, too. Orphaned as a youngster, and left in the "care" of a tightwad, moralistic guardian named Richard Abbey, his real family unit was his two brothers, and he grew up without privilege and with little indication of things to come, remembered mostly by his classmates for his willingness to get in a scrap. The other John, born 145 years later, had it relatively good. He too was a semi-orphan, deserted by his seagoing father and handed over to his aunt Mimi by his party-girl mother, Julia. But he still kept in frequent touch with Julia, and visited her down the street, at least until she was hit by a car when he was sixteen, not long after she first saw his band play. For all the turmoil, Mimi was steady, stern, loving. It is a childhood John would rage against and romanticize for the rest of his short life, and he, like Keats, was a natural fighter, as most Scousers, the proud toughs of Liverpool, learned to be. But while Keats fought in part out of what seemed a natural abandon, an ability to forget himself and throw himself into things, there was, from the earliest days, an edge to Lennon, a chip on the shoulder, and his attacks, most of them verbal, had a black and cutting viciousness. "The only thing you done was Yesterday," he sang to Paul after the breakup of the Beatles, a line that sounds savagely caustic to casual fans but par for the course, if not mild, to those who really knew him. Keats, on the other hand, seemed to belong on that short list of great artists who were also truly good people, and even at his darkest, his bitterness was leavened by charity and empathy.

There is a megalomaniacal aspect to the need to link our own lives to the lives of the great, but Walter Jackson Bate made a career out of extolling the more positive aspects of this linkage: the way we use the great to form our own identities, the inspiration we draw from others to rise above pettiness and the small in general, and the way we can ultimately release our own powers by emulating others. Both Keats and Lennon conceived of the idea—"I will be a great poet/rock & roll star"—long before they began to practice and dedicate themselves to the notion obsessively until, finally, reality caught up. Biographers can't help but describe Lennon's discovery of Elvis, and then Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Buddy Holly, in religious terms. "The Messiah Arrives" is a chapter title in Bob Spitz's biography of the Beatles, and the Messiah was Elvis, followed by his disciples: "To fifteen-year-old John Lennon, the broadcast was some kind of personal blessing, like a call from a ministering spirit." As fans would later do of him, the young Lennon gobbled up every small fact he could about Presley's life, as if these details held a life-changing secret (they did). He was smitten, converted, drunk on both music and the idea of music. We have few details of Keats's early life, but by the time we catch up to him, in his late teens and early twenties, he was fully taken over by what Bate calls "the intoxication with the vision of greatness," and he soon began his long poem,Endymion, by tremblingly hanging a portrait of Shakespeare over his desk and wondering if it was "too daring to Fancy Shakespeare" a kind of talisman to preside over his effort. During those years Keats indulged in behavior that would be familiar to the young Lennon and to many a fan, wearing dramatic and affected clothing that made others stare, daydreaming about times to come ("mad with glimpses of futurity"), and acting in ways that deeply embarrassed him later on, like putting a laurel wreath on his head in the presence of his early mentor, Leigh Hunt.

Intoxication, and the ambition it fuels, may be necessary ingredients for greatness, but there had better be something there to begin with. Long before they wrote anything meaningful, both Keats and Lennon stretched words, playing and punning and rhyming. Keats, writing to his younger sister in a manner that doesn't exactly evoke the great odes, draws to the conclusion of a long poem of near gibberish with:

There was a naughty Boy

And a Naughty Boy was he.

He ran away to Scottland

The People there to see—

Lennon, meanwhile, was to doggerel born. His early love of Lewis Carroll, "Jabberwocky" in particular, is no great surprise, and he was, as Aunt Mimi says, "always inventing daft words." This never stopped, whether quipping at an American press conference, or claiming to be an Eggman or a Walrus, or publishing his two books of nonsense literature, In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works, virtual homages to Carroll, with lines such as "On balmy seas and pernie schooners/on strivers and warming things." Philip Norman tells the story of a young Lennon who, during a dull sermon, picked up a Boy Scout manual and quickly altered "A Boy Scout is Thrifty" to "A Boy Scout is Fifty," drawing laughs from the kids around him. Norman also describes the boy as twisting himself nearly upside down in a chair (a habit he kept up to the end) while reading books with "an insatiable physical hunger," a hunger much like that which drove Keats to gobble up his school's entire library. Both found a sense of adventure in books, and both had an innate sense of the plasticity of language, a sense that was almost made visual, in Lennon's case, on the cover of Rubber Soul (a revision of the album's original title, Plastic Soul). As for molding this plastic language to evoke laughter, Lennon was the far sharper of the two. The Keats that Walter Jackson Bate paints in his pages was capable of suddenly imitating an oboe or a spinning billiard ball or a baby bird, and was always ready to laugh at the jokes of others, but, perhaps due to his charity and straightforwardness, he lacked the edge necessary to cut, preferring humor to wit. Lennon had no such softness. His mates laughed, but warily. He could be a generous friend, a great pal, but he was particularly quick to pounce on the weak. He developed an odd fondness, for instance, for mocking the handicapped.

There is one other quality that the two men shared, a quality that Keats himself defined in one of his most famous letters. That is "negative capability," the capacity to "be in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason." Bate sharpens Keats's definition with his own: "In our life of uncertainties, where no one system or formula can explain everything—where every word is at best, in Bacon's phrase, 'a wager of thought'—what is needed is an imaginative openness of mind and heightened receptivity to reality in its full and diverse concreteness." In contrast, Keats's friend, the stolid Charles Dilke, could not feel "he has a personal identity unless he has made up his mind about everything." Keats had what Bate calls "an adhesive purchase of mind," that allowed him to reach emphatically out of himself—"I can go out of myself entirely and enter into the minds and feelings of others," Keats bragged—in the manner of Shakespeare. It is hard for me to type this line without thinking of Bate himself, who is said to have grown sick and developed a terrible cough as he neared the end of his biography of Keats.

One way that "being in uncertainties" manifests itself artistically is in a tendency, which quickly became obvious in both musician and poet, not to be content with one style or manner and upon completion of a project to turn almost immediately away, sometimes mocking the previous style, while heading toward something new. Of course it is uncomfortable to float unmoored, to resist saying "this is how it is," but for an artist it may be as necessary as it is occasionally unpleasant. Lennon craved and sought answers in Eastern religion, drugs, and romantically naïve concepts of love and peace, but he could never rest long in these certainties before overturning them. The only thing that truly approached religion for him was music, just as for Keats, who never imagined there was a heaven, it was poetry. And both, for all their talent for living in uncertainty, approached their arts from an early age with the intensity and passion of true believers.

Bate claimed that the human mind is more "actively adhesive and projective" than we usually give it credit for, and that it, like a chameleon, is "dependent on what is outside itself for its own coloration." What colored the young John Lennon was rock & roll. It started with an obsessive love of the harmonica, even before Radio Luxembourg whispered its secrets of another world. Then the guitar became the sacred object, to be coveted and secured and played over and over while alone in his room until, finally, it was time to play with others, first with his less-skilled bandmates and then nose to nose with the left-handed fifteen-year-old (almost two years his junior) who would share, to use an appropriately grand word, his destiny. If the physical manifestation of devotion is practice, then young John and Paul were deeply devoted. The two boys practiced at all hours, slavishly imitating the music they admired, barely thinking about the possibility of being original. Keats, too, was hardly an original at the start. Early on he fell under the spell of Leigh Hunt, whose sentimental poems would become and remain the target of mockery, and against whom Keats quickly began to define himself. But, Bate cautions, "we must evaluate influences to the degree that they release energies, and allow one to go ahead on one's own feet." We all need a place to start, and both Keats, and John and Paul, began, naturally enough, by imitating what they knew. In Keats's case this meant working his way through the limp and flowery poesy of Hunt. For John it meant throwing over the old ballroom-crooner crap and immersing himself in "Roll Over Beethoven," "Heartbreak Hotel," and "Tutti Frutti." In short order he and Paul absorbed Chuck Berry, Elvis, Little Richard, Fats Domino, the Everly Brothers, and then a new influence that released long pent-up energies: Buddy Holly and the Crickets. What Holly offered, along with a clean driving infectious sound, was a new possibility: the man wrote his own lyrics. This was unheard of. Every biography says it in one way or another, but Paul puts it most simply: "John and I started to write because of Buddy Holly." Soon came the Lennon and McCartney of legend, sitting beside each other, playing off each other, hammering out new songs—"I'll Follow the Sun," "Love Me Do"—at top speed, the beginning of the great outpouring. Negative capability reigned. Bob Spitz writes: "It was an indefinite, unpredictable process; there was nothing sophisticated about it—no method to speak of, aside from studying other songs—just a general notion of where something was headed." They shared with Keats an ability to write clean, condensed verses, and the ability, often underrated, to write them fast.

They also shared great good luck. Leigh Hunt would become a pincushion for later critics but, without Hunt, Keats never would have had his first poem or his first volume published, and likely never would have met Shelley or Wordsworth. Things had to fall into place for this to work and they did, they did. As for John and the Beatles, their ascension has the improbability of the opening scene of the first Indiana Jones movie: the rolling rock has to fly past them, the spear has to just miss, the right manager named Epstein to suddenly appear, for the adventure to continue on its rollicking way. In fact the whole sequence of events is almost entirely inconceivable, and a thousand things had to fall right for a band from Liverpool to get noticed in London, let alone in the United States, a land where not a single British band had ever made it. Fate again. No wonder John said, quite seriously despite the later denials, that he and his mates were bigger than Jesus.

3. Apprentices

The truth is that fate was not a subject I liked to talk or think about at twenty-seven, four years removed from college and the protective world of Bate and books. I'll admit that I had a quote from Beethoven pinned over my writing desk—"Take fate by the throat"—but that was just so much youthful bluster. At my age, Keats had been dead two years and Mark David Chapman had the same amount of time to regret what he had done, if regret ever flickered through his dark mind. And at the same age, John Lennon was at the height of his powers and popularity, the Beatles having just put out Revolver and, before long, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

My life was going slightly less smashingly. I worked part-time as a carpenter's helper, though I was about to move indoors to become a bookstore clerk. The vainglorious fantasies from college were not dead but they sure as hell had taken a beating. During those days, to think about my life in any large sense, hopes and dreams and all that, was to get instantly depressed, so it was far better to keep focused on smaller matters and short-term goals. The good news, the relative good news, was not a best-selling album or praise from Wordsworth, but the fact that, slowly and stubbornly, I was beginning to put some words down on the page. Not particularly great words, but they were words, and that, I understood, when not sunk low by bitterness and depression, was in itself a small triumph.

I was still hungry for the secrets that the lives of other artists offered. That was why I devoured biographies. I wanted to know how they got from nowhere to somewhere. I'm not talking about lucky breaks, which were beyond my control, but about hard work, the struggle of apprenticeship. That was what interested me more than the immortal poems and timeless songs. I wanted to know what it was like during the trying times, the apprentice years, when all was undecided and futures were being hammered out. This language I'm using now—"fate," "futures hammered out"—is old-fashioned, and that is intentional. Because while many things had to go right in the lives of Lennon and Keats, and many circumstances had to line up, there was also something not so random at work in their stories: an element of will, of effort. Are willpower and effort no more than a particular strand of DNA, a predisposition to hustle? Maybe. But I insist that it also has to be something more. "One of the values again of biography, as of history," Bate writes, "is to remind us that men are free agents: less free, perhaps, than they themselves think they are, but far freer than our academic and rather doctrinaire approaches to them assume."

Yes, that's it. We need to believe, I—sitting at my desk with precious little evidence that I was not insane for choosing such a nebulous and frustrating profession—needed to believe that intention and effort mattered. Needed to believe that trying mattered, even if that was a kind of silly and old-fashioned concept. More specifically, I needed to believe that my repeated efforts, my attempts to throw myself into my work, could result in, if not Beatlemania or immortal odes, at least a book or two.

Which is why my focus wasn't on "Ode to a Nightingale" but on Keats's earlier long bad poem, Endymion. And why my focus wasn't on Abbey Road,but on the hard months and marathon sessions in Germany, before the mania set in. That's what I was hungry for. Those nights on the stage in Hamburg when the four boys were forced to play almost through the night, forced to win over the initially hostile crowd, a crowd of beer-throwers and fighters, forced to find a means of survival. The evolution of that stage act was purely Darwinian, and without Germany the necessary adaptations would not have occurred. The sets were long, the breaks were short; they had no choice but to become both tight and loose, both honing in and airing it out, extending jams to fill time. As a biographer, Bob Spitz is no Walter Jackson Bate, but he is at his best when he describes the Beatles' "baptism by fire" in Hamburg: "Something strangely significant had happened there, something intangible that opened a small window of hope and gave their dreams an unpredictable new lift." Yes, something changed. The fact that they started ingesting speed didn't hurt the overall intensity, but it was much more than that. Whatever the combination of reasons, they returned to England a different band. The screaming began.

John Keats did not take speed or play Little Richard songs late into the night. He left the drugs to his contemporary, Coleridge, and set about his productive way in a more goody-two-shoes fashion, though he shared with the Beatles' baptism a certain imposed rigor. He left London and went to the sea, the Isle of Wight, and dedicated himself to writing a long poem—"Did our great Poets ever write short pieces?"—while setting an ambitious goal of four thousand lines. He rented a room and, to his delight, discovered a portrait of Shakespeare in the hallway, which the landlady allowed him to take and hang over his desk. The long poem did not come easily, the early lines were bad, but he pounded his head against it, proceeding in the willful manner of a hack writer. Bate writes: "He had the instinctive prudent sense that activity and momentum are valuable, and that longer poems provide a spacious field for exercise, tending to prevent constriction and imaginative cramp." He pushed ahead through the next months, retreating from the Isle of Wight but not from the project. He did not want to be a poet in theory but in practice. He vowed not to tremble over every page but to dive straight into the sea, to discover the tides and the soundings by himself rather than sitting on the shore where he might "take tea and comfortable advice." True, the writing was bad, some of the worst writing we have from any major poet, but he suspected, rightly it turns out, that if he kept pushing it would lead him somewhere. And of course it did, though not right away. There was a lag before the poetry showed the benefits from his effort, but right off he gained confidence, momentum, and a tendency to compose quickly, unintimidated by the blank page.

The ragtag Beatles returned from Hamburg with new habits. First the habit of composition, with John and Paul, righty and lefty, sitting close and pointing the guitars at each other, "neck to neck" as Spitz says, filling in each other's words and chords as if they were one artist, moving already away from the early lazy romantic lyrics (even as those lyrics were growing popular). A certain toughness, along with condensation and economy, were won in Hamburg, and now when they stepped onstage they were hardened professionals, able to turn it on without a thought. For Keats, not long after Endymion, there was no more forcing it, and he made a dramatic turn away from romantic dilution and "mere scenery." It was time to leave the cozy drawing-room world of Leigh Hunt behind and begin the journey that ended with the great odes.

4. Glory Ride

My story is really about beginnings, not results, about the sowing of the field, not the harvest. Of course any young artist must imagine that harvest, in fact must see it and exaggerate it in Technicolor terms as a means to keep going during lean times. Keats not-so-secretly dreamed of being a great poet, an ambition that occasionally caused him embarrassment but that, for the most part, sustained him. In these more ironic times we could never admit such a thing without a self-deprecating or sarcastic twist, but you can be sure the same dreams drive many artists just as I know they drive me. As for the young John Lennon, he constantly dreamed of being a rock & roll star, of girls and guitars and cash. Little did he know.

Am I insane? Lennon asked himself as a teenager. It is a natural enough question for any artist to ask before they are recognized by the world. His Aunt Mimi certainly would have said yes, since her young nephew had dropped out of school and cut off all other options. Richard Abbey clearly thought the young John Keats was crazy when, after several years of studying medicine, the boy turned his back on the profession to pursue, of all things, poetry. Abbey expressed his displeasure by tightening the purse strings of Keats's parents' inheritance. Clearly the state of mind of the young artist is something close to insanity, if by insanity we mean a belief system built upon the irrational and unknown. Keats's story is remarkable, in part, because of the commonsensical and thoroughly sane way in which he approached his insane time.

A different madness greeted Lennon and the Beatles at the next turn of their story. There was something they brought back from Hamburg in addition to good work habits and stage presence, and that something was haircuts. Philip Norman cites Valentino and Sinatra as precedents of fan worship, but I think it is fair to say that, thanks to the advancement of media and the crush of population by the early '60s, the world had never seen such an outpouring of adulation as it saw with Beatlemania. The fans who chased the boys might have looked cute in the movies and on newsreels, but it quickly became apparent that there was real danger. Crowds knocked over barriers, grabbed for the boys, screamed during concerts so that no songs were actually heard, and because someone—George?—mentioned that he liked jelly beans, threw these hard candy missiles at the stage throughout their concerts. The fifteen-year-old John focusing on Elvis and the young Keats hanging up Shakespeare's picture are one thing, but this—the fainting, the screaming, the hurling of oneself into police like berserkers—was another. Or was it? Maybe the fans were not studying the Beatles to become great artists, but over the next few years many of them picked up guitars, most of them changed their hairstyles, and they all clearly wanted to change their lives. There might be little that was subtle about their behavior, but if we view the phenomenon generously, we could say that these fanatics, these followers, were also hunting for art, and biographical information, that they could put to use.

It is remarkable how soon things went sour in John Lennon's mind, how quickly the crowds began to seem Kafkaesque; the partnership with Paul turned ugly; the mind weeds, fertilized by drugs, took over. But oh, that year or so when he went, in a mad rush, from dreaming the dream to living it. Most people, including Keats, never get to experience a physical manifestation of their deepest dreams, and it is hard to get one's head around what the sensation must have been like. Biographers of the Beatles and Lennon consistently use words like "euphoric" and "ecstatic," and that sounds about right. And here, too, the early years, the apprentice years topped off by Hamburg, held them in good stead. One-hit wonders and successful first novelists often share an uneasy creative reaction to fame: they are nonplussed, anxious to recreate the first success. The Beatles had no such problem. The habits of composition and performance were in place, the trove of songs was burgeoning, and they greeted the challenge of creating new albums with more excitement than anxiety.

The roll began, aided by a happy confluence of drugs. The Beatles were lucky here, too. Whiskey, Coca-Cola, and speed, the staples of the early concerts, were perfect for staying up late and performing onstage. But at the end of the second American tour, huddled in their hotel room and beaten up by a series of concerts that sometimes felt like a mugging, almost ready to turn away from touring altogether, a man named Bob Dylan handed them a joint and everything changed. Twin influences were at work on John here. Pot and acid prevailed during the coming studio years, and almost as mind-bending was the monumental influence of Dylan. In fact had John not already had his artistic legs, Dylan would have knocked him over, or turned him into a nasally clone. As it was, John's world swerved, but having undergone his apprenticeship, he made it swerve for him. He returned to his Jabberwocky roots to swim in a river under tangerine trees and marmalade skies.

For the young poet, there was no Keatsmania. His timetable was short, ridiculously short, and the plaudits would be almost entirely posthumous. When they did come, with Keats long buried in the ground—"To thy high requiem become a sod"—the romantic image of the poet bore more than a mild resemblance to a modern rock star. Long hair flowing, young, romantic, starry-eyed, and, of course, tragic. For the next two centuries, Keats was the subject of tributes, biographies, and movies; non-poets know the basics while working poets point to his life as an allegory of what is possible. That he knew nothing of his fame is depressing, but not devastatingly so. If he did not experience the pleasures of recognition in his life, he did experience the thrill of high creation. After Endymion he began, as he later advised Shelley, "loading every rift" of his subject "with ore." He wrote one of the most famous poems in the English language, "Ode to a Nightingale," in a single morning. The limp, flowery lyrics of Endymion were gone, and in its stead were lines like these:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves has never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies.

The themes of the great odes sound familiar to us now. How does an artist lift himself out of his own time and life through a kind of communion with art? Is it possible for us to transcend the merely human through song or are we all forced to accept the larger processes of life, the deep uncertainties, which also means accepting death as part of the process? And is this kind of slipping sense of process, of constant change, all there is, or can art briefly capture and hold what is so elusive?

A deep sense of how precarious life is filled the mind of John Keats, only twenty four, a sense that was not unnatural for a boy who had lost both parents and had just watched his younger brother, Tom, die from the same illness that would soon claim him. It was a quality he shared with John Lennon, who fell into a deep depression when his beloved though inconstant mother, Julia, was taken from him a second time. The fans might have thought Paul was dead, but it was John who obsessed over and worried about death. Though essentially healthy-minded, Keats could not help but feel death encroaching on not just his life but his art. He was no fool and when he coughed up blood in February of 1820 he knew what was what, saying with typical directness: "That drop of blood is my death warrant." A year later he was dying in Rome, his remaining brother, George, thousands of miles across the sea, a homesteader in Kentucky.

Looking back over the lives and tragic ends of the two Johns, there are too many connections to list (for instance, the troubled role of money in the lives of these two English poor boys) but one that I can't help but mention is the fact of their famous lovers, both readily known, to most, by a single name. Yoko, like Fanny before her, was roundly mistreated by both fans and intimates of the men. Bate describes how Fanny Brawne fared poorly during the Victorian era: "Few women have had their memory more harshly treated without justification than Fanny Brawne for the first century after Keats's death." We all know how Yoko fared. Bob Spitz's biography of the Beatles concurs with the common impression, calling her a "malevolent omnivore," though Philip Norman, in his recent Lennon biography, is more generous. Perhaps more important, as far as posterity is concerned, is how John felt, and, even more to the point, what he wrote. "Woman," for instance, a song that seems to embody Lennon's final incarnation as the blissful, stay-at-home family man whose wife has remained an inspiration for over a decade, a union that by then had lasted longer than his with Paul. Keats's letters to Fanny endure as well, perhaps the most famous love letters in all of literature. But no sooner was that engagement to Fanny Brawne made than the bloody cough came. Keats was not as famously jealous as Lennon, but his profusions of love are intertwined with darker thoughts: "In case the worst that can happen, I shall still love you—but what hatred shall I have for another!" Like the very young man he was, Keats not only looked forward to their life ahead but fretted about being settled and the loss of his freedom, though these were worries that he would never have to face. We are reminded that however brief Lennon's happy family period was, however horrible his death when he seemed to have found some peace watching the wheels and playing with his young son, that his time far surpassed the portion that Keats was given. Keats, in contrast, remains forever a young man, never escaping his twenties, and, like the figures on the Grecian urn, or like those on an album cover, never grows old.

When the two men died, they left more behind than bereaved lovers and relatives, distraught friends, and great poems and songs. They left behind a burden. Which is to say that the poets and musicians who came after, though admiring and gaining inspiration from the work, would also be intimidated by it. While Chuck Berry and John Milton might have freed our heroes, released something in them, it is equally possible for artists from the past to paralyze those of the present. This is the subject of the small book that Walter Jackson Bate published in 1973, The Burden of the Past and the English Poet. The problem of how to create original work while looking back at such a rich legacy of things already done, is particularly acute in modern times, exacerbated by our emphasis on being original. Often the answer for the artist is to retreat into a small fiefdom, a sub-genre, and refine and develop that small plot, tending one particular strand of roses. It was a tendency that Keats saw in his contemporaries who, compared to the Elizabethans, seemed "as a petty ruler, like the Elector of Hanover, to an emperor of vast provinces." Two hundred years later the modern poet is, of course, even more cowed into feelings of impotence and irrelevance, no longer one of the world's rock stars (rock stars aren't even rock stars any more) and seemingly forced to reign over a province the size of a metaphorical Rhode Island.

Bate, not surprisingly, pointed to Keats when suggesting a way out of this dilemma, a way that influences can be incorporated and overcome. Even at the beginning of his brief career, Keats had an awareness that poetry was a fallen art that might never again reach the heights of Shakespeare and Milton, but rather than being paralyzed by this fact the way his contemporary Coleridge was, he proceeded briskly, looking to the past greats for solace, guidance, and inspiration. As Bate argued, it is by honestly facing up to great predecessors—"a direct and frank turning to the great"—and engaging in a dialogue with them, that we overcome the burden of the past and begin to create something new. Obviously it isn't as simple as pinning a picture of Shakespeare to the wall or listening to "Heartbreak Hotel" over and over, but the hope is that by involving oneself in a discussion with artists who came before, a kind of talking to ghosts, one might eventually begin to establish one's own identity, while simultaneously steeling oneself against the whims of the present. In Burden's rousing conclusion Bate suggests that what is required is a deep honesty and a "personal rediscovery of the great," as well as "boldness of spirit," a boldness that "involves directly facing up to what we admire and then trying to be like it." As simple as this might sound, it is also radical today in a time when the concept of originality is overvalued. Bate writes: "None of us, as Goethe says, is very 'original' anyway; one gets most of what he attains in his short life from others." Why should literature or music be so different than other human endeavors—sports, say, or carpentry—where we naturally learn from those who came before? Isn't it always through others that we begin to define and become ourselves?

5. In the End

The human imagination, at least as Walter Jackson Bate described it, has a kind of living, restless, animal quality. Yes, it takes the color of what is near it in the manner of a chameleon, but it is also ever hungry, eager to feed, unable to stand still. One direction it might choose to roam is toward bitterness, toward What if, and this is natural enough if the breaks don't come, if you feel the hand you are dealt is not the one you deserve. Certainly, there are people who can't be blamed if their minds move that way, like poor Keats near his end or like Pete Best. As Bate liked to say, channeling Samuel Johnson, there is really nothing to envy in others anyway, as all of our stories, however blessed, have the same ending. And if the imagination is really an animal, one direction it can be nudged, or prodded or pushed or whatever one does with this particular animal, is away from bitterness and envy and toward the making of art. There lies a thrill and a pleasure that has at least a little less to do with luck and fate.

I am Bate as Bate is Keats as Keats is John and we are all together. I end with the picture of Walter Jackson Bate lying in his room, coughing, though not quite able to cough up blood, the animal that is his imagination colored by Keats's end. I end with the young John Lennon, memorizing the smallest details of Elvis's life, dreaming his own life as a rock star into being, and of the young Keats, wearing his laurel wreath with Leigh Hunt, giddy with the possibility that he might one day approach the greatness of the poets that he admires to the point of worship. I end, despite the times, unembarrassed by my own continuing obsession with the lives of those who have achieved extraordinary things, with the lives of the great. I end with an ode to striving, to effort, to will, and with a song that I believe is the most interesting and enduring song of all: the song of beginning.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.