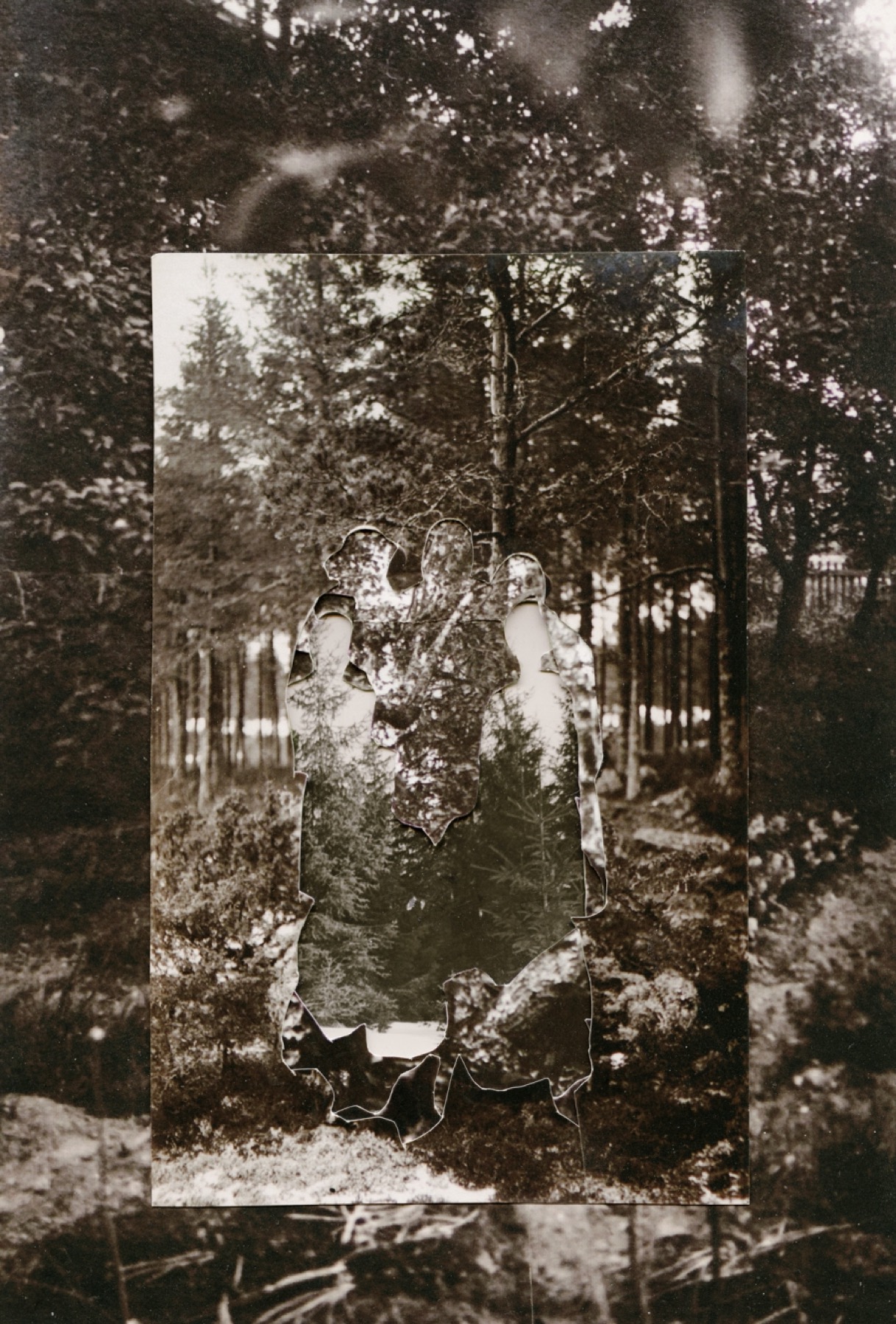

Art by Anni Leppälä. Courtesy of the artist and Purdy Hicks Gallery, London

Pilgrims of the Lost Cemeteries

By Christina Cooke

The closest the Cable sisters can get to home these days is by floating above it in a boat. This is how they spent the third Sunday in May, reminiscing about what lay beneath Fontana Lake back when this North Carolina land was a spring-fed family farm ringed by mountains. “Our house sat right out here and under the water about forty or fifty feet deep,” said Helen Cable Vance, pointing over the edge of a twenty-four-passenger pontoon boat to the rippled water’s surface, where a brown log house with a red-shingled roof once stood. It was a drizzly morning, and the shore, one hundred yards away, was deep green, punctuated by the round white poof balls of the mountain laurels in bloom. “In my mind’s eye, I can see the potato field right behind the house,” Helen said. “I can see the apple trees, and I can see the barn and the cattle and the crib.”

Helen and her siblings, now in their eighties, grew up in this cove in the 1920s and ’30s, though they called it a holler then, before the Tennessee Valley Authority dammed the Little Tennessee River to produce hydroelectric power for the war effort and for customers throughout the Southeast. When water began backing up into the valley in 1944, a number of family farms, settlements, and towns were submerged. Property above the high-water mark on the north shore—including twenty-eight cemeteries and more than one thousand graves—was absorbed into Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Despite a contentious, decades-long fight, the major road through the area, NC 288, was never rebuilt, making the land inaccessible by motor vehicle.

I first learned about the flooded towns when I was fourteen, on a summer vacation in the Smokies. As my family and I were hiking along a trail through the hardwoods along the north shore of Fontana Lake, we stumbled upon the rusted skeleton of what was likely a Model B Ford from the early 1930s. Though the windshield, windows, and wheels were absent and the doors were detached and lying in the leaves, the cab and hood remained mostly intact. This vehicle had likely broken down, my father explained. Because gas and tires were difficult to come by during wartime, the owner had probably not been able to return for the car before access was cut off for good. The out-of-place vehicle—and the stories its presence suggested—held my fascination for years.

Now it’s difficult to piece together information about the people who once occupied these mountain forests. In pursuit of a wild, natural state for the new section of national park, the government was thorough in its removal of physical remains. Residents were asked to pry apart buildings and carry the lumber away, and the structures that remained were burned to the ground. “They wanted wilderness and to get rid of everything they could,” Helen said. “But they can’t do away with everything as long as we’re living. We’ve still got it in our minds. We know where we lived.”

Bright and full of energy, Helen and her sisters, Mildred and Darleene, described to me their front porch swing, the washbasin under the oak tree, the potato patch, and their thirty-nine stands of bees. They recounted the tree with the crooked trunk that marked the way to the family cemetery and the Indian trade beads Aunt Prudie used to find on the property. They remembered the times, after the property was flooded, when the TVA would draw down the lake to inspect and maintain the dam—they would boat partway, then walk across the exposed lakebed to their old home place, where they would find artifacts from childhood in the lake-bottom sediment: glass marbles, the leg of a porcelain doll, the wheels of a tricycle, the smooth white stones that had lined their mother’s flowerbed. Their voices carrying across the surface of the water, the sisters recounted details and told stories, breathing life and nuance into a land whose variations have been filled in and covered for more than seventy years.

The Cable sisters’ great-great-grandparents Samuel and Elizabeth migrated from Cades Cove, an isolated valley in the mountains of eastern Tennessee, into the wilderness of Swain County, North Carolina, in the mid-1830s. They arrived soon after the federal government forced the Cherokee, the area’s original occupants, to territory west of the Mississippi River along the Trail of Tears. They were the second family to settle the Hazel Creek basin. The Proctors came first.

Like many families in the area, the Cables survived as subsistence farmers. The sisters’ father, Jake, a natural-born storyteller, ran the farm and worked as a planer for the W. M. Ritter Lumber company. Their mother, Sarah, taught school until she married. On the farm, they grew peas, carrots, onions, corn, and sweet potatoes in large gardens, picked berries from the wild, and canned everything they could. They kept cattle, hogs, and chickens, and their grandfather was known for his success as a bear hunter, killing more than one hundred in his time. In a blacksmith shop on their property, the men hammered their own tools and plow points, and when the children’s shoes wore out, their father would resole them. “In the Thirties, you had to do your own thing,” Helen said. “There wasn’t much buying in those days.”

When the sisters and their older brothers, Clyde and Guy, were young, their lives centered on school, church, and farm chores. They walked three miles to and from the one-room Fairview schoolhouse for elementary school. Later, they walked to Proctor, population 1,000, for high school.

For fun, the children played hide-and-seek, traversed the forest through high tree branches, played games with balls they fashioned by wrapping pieces of rubber in twine, and crafted toy geese, foxes, horses, and hogs out of corn stalks. The family would sometimes visit an uncle in Cades Cove, leaving home at six in the morning, walking twenty-five miles over Native American footpaths, and arriving in time for a late dinner.

Helen was a particularly good shot and by age fifteen or sixteen, she was capable of shooting clothespins off a clothesline from a respectable distance, said her daughter Leeunah Woods. “She was a lady, but she was a little bit tomboyish too. She’s outgoing, but she’s cautious. And if she believes in something and knows she’s right, she’ll fight for it until the day she dies.”

When World War II began, Clyde and Guy left to serve in the Navy, and Jake took a job building the Fontana Dam four miles downstream from the family homestead. Initiated in January 1942—three weeks after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor—the dam was intended to supply hydroelectric power to the Alcoa aluminum plant in Tennessee, which churned out metal for military aircraft. Locals learned after the war that the dam also supplied power to the top-secret Manhattan Project production site in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which developed the atomic bomb.

By 1943, the dam-building project was employing 5,000 men, seven days a week, in around-the-clock shifts. Jake started out as a jackhammer operator and later helped mix and pour the three million cubic yards of concrete that went into the project. The 480-foot-tall structure—the tallest concrete dam east of the Rocky Mountains—was complete in November 1944. Once kicked into operation, it would flood 10,230 acres of land to an average depth of 130 feet, creating Fontana Lake, which is about thirty miles long. It would also displace 1,311 families from the land they had occupied for generations.

The Cable family was saddened at the prospect of leaving the farm—not least because they were paid only $8,000 for their sixty acres of property, a sum Jake and his seven siblings split among themselves. Though Jake helped build the dam, he was especially upset about the uprooting, Helen said, because he, his father, and his grandfather had lived on that property their entire lives. “It was sad for us kids too, because we were going to lose our classmates and cousins, and we didn’t know if we’d ever see them again,” she said. “But children adjust better to things.”

Despite their sorrow, the family prepared to leave without protest. Helen helped her father disassemble the family house, nail by nail, board by board, and pack the lumber into a truck they borrowed from a friend. Then she gathered two keepsakes—a small plastic lamb she got for Christmas one year and a five-sided medicine bottle her grandfather gave her—and moved with her family to a four-bedroom house on an acre of land in Sylva. By late March 1944, the Cables had left Hazel Creek and the family farm forever.

In addition to holding the resting place of their ancestors, the Cable family’s land bore years of fond recollections—playing marbles in the yard, tending vegetables in the garden, taking long rambles through the woods. After they left the farm, the family occasionally borrowed boats to visit the north shore of the lake, but true access always seemed just out of reach. “We’d look across the lake and get so homesick,” Helen said.

At a family reunion in a campground near the lake in 1976, the Cables decided to take action—to organize the first Decoration Day in thirty years. According to Alan Jabbour, former director of the American Folklife Center and author of the book Decoration Day in the Mountains, Decoration Day has been practiced in the rural Southern Appalachians since before the Civil War. It is the basis for Memorial Day, though the national holiday is slightly different in that it focuses on those who died during military service and has less of a religious association. On a community’s annual Decoration Day, which usually occurs in the late spring or early summer, people visit family and community cemeteries to clean, maintain, and decorate the graves as well as hold small religious services, sing gospel songs, and partake in a meal called a “dinner on the ground.” A Decoration Day celebration is about piety, Jabbour says, about taking the time to demonstrate respect and “maintaining a close sense of connection with your community, and not just the living but also the dead.” In some parts of the South, graves may be festooned with blankets of flowers.

Growing up in the twenties and thirties, the Cable sisters came to Cable Cemetery the fourth Sunday every May for Decoration Day. Months in advance, their mother, Sarah, would sew a new dress for each of the girls, creating her own patterns based on the styles she found in the Sears Roebuck catalog. The children would fashion crepe-paper flowers with wire stems—roses, peonies, gladiolas, dahlias, and sweet peas—to lay on the graves, dipping the finished products in wax to protect them from the rain. Sometimes they made flower-covered wreaths, as well.

In April 1978, Helen, Mildred, and a few others piloted a boat to return to the cemetery and check on its condition. When they reached the ridge-top burial ground, they were horrified. “It would break your heart,” Helen said. “A third of the monuments were half-turned or turned over. It was in bad disarray. And little shrub pine sprouts were growing all over it.”

For help, the sisters called the National Park Service. At the time, the NPS refused to transport former residents across the lake, but they did agree to clean up the cemetery. (“It was clean as a pin!” Mildred said.) Helen and Mildred arranged their own transport, set a date for the decoration, phoned relatives to let them know about it, and placed newspaper, radio, and TV ads to get the word out. On the fourth Sunday in May 1978, more than one hundred family members showed up, and several people with personal fishing boats shuttled everyone back and forth across the lake. “Everybody was so thrilled to get to go back,” Helen said. “I took my daddy’s younger sister, and she was just like a little kid going through there.”

Spurred by the success of the venture, the sisters organized another decoration at the nearby Proctor Cemetery. The following year, they arranged a few more, and the year after that, they held decorations at all twenty-eight cemeteries, all of which are on the north shore, transporting motorcycles and wagons across the lake to carry elderly pilgrims unable to walk the long distances between drop points and gravesites. A year or two later, Helen and Mildred founded the North Shore Cemetery Association, made up of former north shore residents and their descendants, and together the group petitioned the Park Service for better access to their ancestral land. While they were never able to secure a road, they did reach a compromise that grants them limited access to the territory: since 1980, Park employees have kept the cemeteries clear of leaves, weeds, and fallen limbs throughout the year. They provide boat and ATV transport from April until mid-October. “They’ve been real good to work with,” Helen said, “but we had to push them for everything we’ve got.”

When I went to the Fontana Basin on the third Sunday in May, I woke up early and drove deep into the mountains from my sister’s house in Asheville. Eventually, the roads narrowed and the trees thickened, and I turned right onto gravel.

I found the extended Cable family mingling on a boat ramp along the south shore of Fontana Lake. A light rain was falling. I approached Helen, who was juggling an umbrella, a folding stool, a walking stick, and a canvas tote bag of artificial flowers. She welcomed me and gave me the lay of the land: she pointed out her sisters Mildred, Darleene, and Eleanor, and her cousin Joretta, who grew up in another abandoned north shore town. “We’ve got some cousins from Tennessee here also,” she said, excitedly.

A pontoon boat named Miss Hazel carried us across the lake and dropped us off at a narrow opening in the trees along the north shore. Lugging bags, coolers, and chairs, we ascended the half-mile trail through the woods on foot. The ground was covered in a soft bed of pine needles, and the green leaves glistened from the rain. Partway up, Helen, Mildred, and Eleanor zoomed by us on ATVs driven by uniformed Park Service employees. The sisters appeared to enjoy the ride immensely.

Cable Cemetery sat in a clearing at the crest of a hill. The sloped ground was mostly bare, save patches of light-green moss creeping in at the edges. “There’s five generations buried here in this cemetery,” said Helen, carrying her large bag of flowers onto the bare red soil. Of the nearly 156 graves scattered throughout the burial ground, all but about twenty-five are relatives of Helen and her sisters.

“That’s my great-great-grandfather and -grandmother,” she said, pointing out the already decorated tombstones of Elizabeth and Samuel Cable, who died in 1877 and 1887, respectively. She bent down and pressed the stem of a purple flower into the soft clay ground before a neighboring plot. “I’m gonna put a flower on this one since it doesn’t have but one on it.”

“Helen,” Mildred called from about ten feet away. “We need a marker here, for these unknowns.” She pointed to a cluster of unmarked graves around her.

Mildred said she and her family have never questioned the importance of paying tribute to deceased family members. “The Lord’s been good to us, watching over us all the time. And those older-generation people blazed the trails for us—it was wilderness in here,” she says. “We were taught to honor our dead and care for our history.”

In the cemetery, Helen rested her fingertips on the top edge of a gravestone that had a garland of flowers carved across the top. “Right here is my brother’s grave,” she said. In conversations about the graveyard, the Cable sisters frequently mention their baby brother, who died the day he was born, on February 1, 1924. The gravestone inscription—which reads “Sufford Lee Cable”—is misspelled; his name was Shufford. “It always irks me,” Helen said, stooping to push another flower into the ground.

As rain pattered on a large white tarp strung in the trees above the picnic tables outside of Cable Cemetery, Helen offered a formal welcome to more than seventy-five pilgrims, both hands resting on the cork end of her walking stick. Holding tattered hymnals, a small group sang gospel songs including “I’ll Fly Away” and “When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder I’ll Be There.” A tall man with a white goatee delivered a message about the Cable family’s legacy and the coming of Christ to judge the quick and the dead.

When the service concluded, participants spread colorful cloths across the tables and scooped pulled pork, collard greens, and creamed corn onto sectioned Styrofoam plates. Someone invited the park workers to join. (“We got those park boys spoiled,” Leeunah observed as the uniformed men filled their plates.)

While a lot of the sisters’ contemporaries participated in the decoration pilgrimages of the early years, many people who were born and raised on the north shore have now died. In recent years, the four Cable sisters have found themselves among the last who know first-hand what life was like there before the flood.

Though their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren attend the decorations, most are not regular about their visits. The sisters realize that young people’s lives are busy, but they worry that the next generations won’t pick up where they leave off. If Helen could impress upon her descendants a single message regarding the tradition she and her sisters have fought to preserve, it would be this: “Remember our relatives and ancestors, and do things to honor them,” she said. “Remember from where you come.”

As the visitors finished lunch, they packed their things and headed down the hill to catch the shuttle across the lake. I stayed with the sisters, who lingered at the cemetery, now dotted with vibrant yellows, reds, oranges, pinks, and purples.

After a while, we migrated down the hill and boarded the boat. As we glided across the wide water, the elements that had infused the ceremonies—history, memory, nature, and imagination—began to give way. Yet the strength of the Cables remained. Their story is reinforced by the time they spend reflecting on the people and place that tie them together. On the ground where yesterday holds as much sway as today, they absorb their family history. And they remember who they are.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.